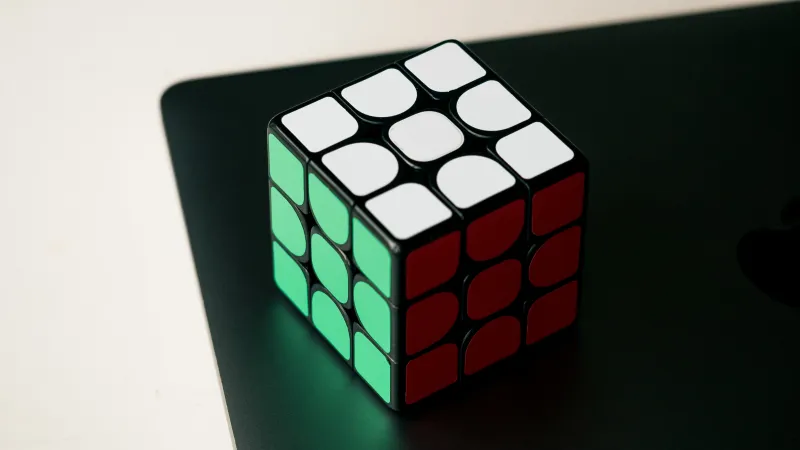

Rubik’s Cube in disarray again

January 8, 2026

One of the core concepts in patent law is the so called “patent bargain”, according to which an inventor is granted a time-limited monopoly in exchange for disclosing the invention to and therefore benefitting the public. To prevent the circumvention of the time-limited monopoly, the Trade Mark system excludes functional marks. The exclusion is contained in Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of the European Union Trade Mark Regulation. The exclusion is absolute and can therefore not be overcome by evidencing that consumers recognise the shape as source identifying.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has a long-standing practice of considering how a three-dimensional mark is in fact in use rather than limiting itself to the representations and descriptions filed, so as to avoid circumvention of the exclusion due to incomplete information. This practice had already led to Spin Master’s downfall in the Simba Toys (Case T-601/17) as it wouldn’t have been clear from the representations in the application that the shape and patterns were essential to how the RUBIK’S Cube works.

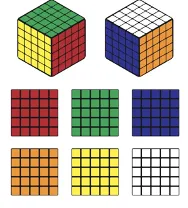

Having awaited a final decision in the above matter, the Cancellation Division resumed invalidity proceedings brought by Verdes Innovations SA, a Greek producer of rotational puzzle cubes, in January 2013 and declared the following registrations in respect of class 28 goods (‘Toys, games, playthings and jigsaw puzzles, three-dimensional puzzles’) invalid:

EUIPO registration No. 9975681

EUIPO registration No. 5696232

EUIPO registration No. 9976135

(Case T‑1172/23); and

EUIPO registration No. 9976788

Spin Master appealed and lost. In essence, the Board of Appeal concluded that the six different colours as an integral part of the shape were necessary to obtain a technical result.

On further appeal the General Court clarified that the six colours and their alleged arrangement are of secondary importance because the colours are basic, the representations do not show a specific arrangement and the chosen type of mark and description do not suggest that protection was primarily claimed for the surface design. What does constitute an essential element according to the Court is the contrasting effect resulting from the colour differences, which is inseparable from the shape.

The Court further confirmed that the actual goods and their perception by the relevant public may be taken into account in determining the essential characteristics and the technical result they achieve.

The Court endorsed the technical result as described in the previous decision T-601/17 as a ‘game which consists of completing a cube-shaped three-dimensional colour puzzle by generating six differently coloured faces’ through ‘axially rotating, vertically and horizontally, rows of smaller cubes of different colours until the nine squares of each face of the cube show the same colour’.

The requirement that the shape of the goods must be necessary to obtain a technical result is not to be understood as meaning that other shapes must not achieve the same result. It is irrelevant if those essential elements also have aesthetic appeal or if they create an ornamental image. Registrability can only be accepted if decorative, non-functional elements play a vital role in the shape of the goods as this would not limit the competitor’s ability to develop sufficiently different solutions with a comparable functionality.

Finally, the Court rejected the argument that the exclusion does not apply to all goods in class 28 and in particular not to “jigsaw puzzles” because the registration in question was a three-dimensional mark and the possibility of dis- and reassembling of the of the cube to make the perfect picture could not be excluded. Accordingly, all of class 28 was invalid.

This decision shows the rigorous examination to prevent circumvention of the time limitations provided by other IP rights. ‘Shape’ is not to be understood in a narrow literal way and simply adding colour to a three-dimensional shape cannot negate the applicability of the exclusion. It is always important to determine accurately what is meant to be protected and to consider which type of trade mark may achieve the most fitting protection. And of course, evidence of acquired distinctiveness is not a fall-back for Article 7(1)(e) and could not even rescue Mr Ernő Rubik’s iconic cube that was successfully marketed since the 1980s and is still going strong today.

You may also like