Apple’s Second DMA Compliance Workshop: An Aggressive Defence of Rights

July 18, 2025

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) became entirely applicable on 7 March 2024 for most gatekeepers. By then, the gatekeepers issued their compliance reports documenting their technical solutions and implementation of the DMA’s provisions under Article 11 DMA as well as their reports on consumer profiling techniques as required under Article 15 DMA. A year later, six gatekeepers submitted an update to the first version of their compliance reports (they can be found here).

I will be covering this year’s compliance workshops held by the European Commission, where the gatekeeper representatives meet stakeholders to discuss their compliance solutions to the DMA’s obligations (and the updates they introduced since 2024). This piece covers the EC’s compliance workshop with respect to Apple’s technical implementation of the DMA. The workshop’s agenda spanned anti-steering, app store rules, interoperability, web browsers, and data portability.

An un-Apple bureaucratic process

During Apple’s first intervention, its legal representatives drummed our ears with a speech we had already heard last year on the first iteration of its compliance workshop. Apple is concerned with upholding its core values, i.e., the ability to innovate from its trusted app store platform and operating system through easy-to-use applications, whilst keeping privacy and security risks at bay, before the EC’s steps in applying and interpreting the DMA. Privacy, security, and safety were buzzwords that floated around Apple’s initial speech, as they did last year.

The gatekeeper termed the EC’s efforts in taking the DMA provisions into reality as undermining Apple’s uniqueness. In that sense, its legal representatives argued that the EC is achieving to produce carbon copies of gatekeepers’ business models. In other words, the DMA suggests that, progressively, the gatekeepers resemble one another, to the point where they might become conflated in their service offerings.

Having said that, Apple went into detail relating to its approach to vertical interoperability, as required by Article 6(7) DMA. To this call, the EC already exercised its non-punitive powers via its specification proceedings, where it set out what implementation measures Apple must abide by to meet the effective interoperability mandate established in the provision. In particular, those implementation measures touched upon two distinct aspects relating to Apple’s approach to Article 6(7) DMA. First, Apple’s request-based process by which developers must ask for access to software and hardware features reliant on its designated operating systems (iOS and iPadOS) on an equal footing to the gatekeeper’s own access to those same features and functionalities, as I discussed in a paper at the start of the year. Second, the features available to developers operating third-party connected physical devices, such as smartwatches, rings, or headsets.

In short, both sets of decisions (which can be found here and here) basically set out a general principle that Apple must comply with to meet the high standards set by the EC. It must roll out, without any significant delay, the same features and functionalities it offers on both its designated operating systems so that developers can incorporate them into their own apps and services. When asked by workshop participants, Apple ensured that it did comply with the ‘free of charge’ requirements set out in Article 6(7) DMA, but it reiterated that it would not make its IP rights available for free.

In Apple’s own view, the EC engaged in a creative interpretation of the law and felt especially worried that its products were beginning to be designed by lawyers, instead of engineers. For the most part, Apple constantly undermined the EC’s role as a regulator and pointed out that it had set out those implementation measures without taking recourse to the experts in the field of cybersecurity, data protection, or telecommunications.

On top of that, Apple criticised the selective approach of the DMA as a piece of regulation insofar as it laser-focuses the imposition of its remedies to create outcomes for a few developers, as opposed to the millions of them that rely on its services every day. In the case of vertical interoperability, such an impact was quite evident, since niche interoperability requests are processed to benefit the needs of a couple of developers at most, vis-à-vis the thousands of developers relying on its App Store and operating systems to operate their apps and services.

Aside from this unintended effect on the DMA’s application, Apple additionally pointed out that a necessary consequence of the EC’s wide interpretation of the terms in Article 6(7) DMA meant that it is trapped between a rock and a hard place since it cannot roll out all the features it would want to in EU as it does in other jurisdictions (e.g., the US). Some examples provided directly by the gatekeeper included its Apple Intelligence feature, its integration of AI into its operating systems, which was shipped in the EU in April 2025, whilst it was already available starting in October 2024 in the US. The gatekeeper’s legal representatives raised similar concerns with its recently announced Visited Places tool, which it announced at the start of June, allowing its Maps app to remember the places where a user has been to improve daily commutes.

Ironically, Apple’s legal representatives responded time and again that they would not expand their DMA compliance solutions to any other jurisdiction when asked explicitly by stakeholder participants. It seems that hindering innovation only goes one way when the EU hinders it, but a race-to-the-top in terms of addressing market power through unifying global markets does not rank high on Apple’s plans.

Alternatively, asked by stakeholder participants about the testing of their interoperability compliance solutions, Apple legal representatives blamed (once again) the regulatory process and the EC for uprooting their core values. Prior to the DMA, according to one of its legal representatives, Apple did not ship every single feature it worked on, even though it did release them on beta versions. Depending on their performance and adherence to its privacy and security standards, Apple decided to discard some features, even if it had dedicated substantive efforts and investments in developing them. That is no longer possible with the DMA since it is currently being locked in by the specification proceedings to ship those solutions regardless of their real-life testing.

Despite those disagreements, Apple went on to present the changes it had already introduced to its compliance solutions as a consequence, such as the introduction of an engineering team focused on ensuring that Apple provides third parties with effective interoperability in terms of speeding up (and marching through) the design and release process embedded into its request-based process (page 156 of its 2025 compliance report). In this same sense, the gatekeeper’s legal representatives walked all of us through the steps that a developer should take to request interoperability for a particular feature. The established and separate engineering team deals with these incoming requests to ensure effective interoperability with newly released hardware and software features in a timely manner, taking into account the stability of its operating system as well as the safety and privacy of its users.

On this same note, Apple highlighted its introduction of the Interoperability Request Tracker (that the EC required it to introduce in its specification decision, para 367 of its request-based process specification decision), enabling developers to receive information on all ongoing requests and already available features to iOS and iPadOS. On this particular point, stakeholders pressed Apple on the fact that its tracker is not really transparent or dynamic in its approach, since it is a static PDF document including the information, without any search, interactivity, or filtering functionalities to enable third-party developers to access data more easily.

Against this framework, Apple presented the rough numbers of the requests that it had been receiving during the last year. On one side, it presented some discouraging news to the DMA enthusiasts. Reality always trumps the hard facts of the law. The gatekeeper’s legal representatives mentioned that they had received quite demanding petitions from developers requesting access to non-existent functionalities. For instance, gaming developers asked for functionality to perform storage externally (and not on-device) or requested access to the COVID-19 contact tracing feature to enable users to interact with real-world humans they met on the street. Before this wave of requests, Apple stressed its wish for the DMA not to undermine the GDPR and its standards by mandating more access in exchange for burdensome access that did not match its own reality.

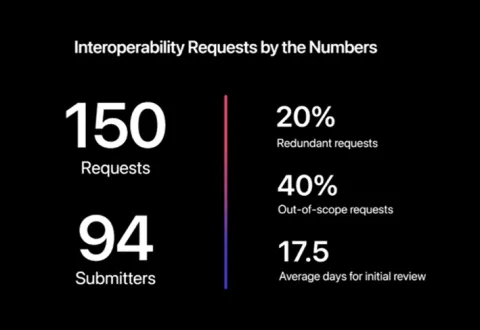

On the other side, Apple put forward the actual numbers of the interoperability requests that it had received until a couple of weeks ago. For the most part, those did not provide an encouraging perspective to the DMA’s application either, as you’ll see from the image below. Most requests (up to 60%) amounted to access that was not even formulated in form (redundant requests) by the developers, or that fell outside of the provision’s scope altogether. Aside from the negative news, however, Apple did present a story of success of its interaction with developers when they requested access to vertical interoperability, such as a use case where a developer wanted to access the Critical Messaging API to create apps and services to notify its employees in case of dangers to their security and safety.

Furthermore, Apple also discussed in its (lengthy) presentation at the start of the workshop the features that it was forced to provide interoperability with, in the terms presented by the specification proceeding targeting third-party physical connected devices. For instance, Apple highlighted both iOS notifications and Wi-Fi history as two main points of contention that it already held against the European Commission for going too far in terms of the requirements it imposed on them (e.g., the EC required to decrypt the iOS notification function to enable better pairing with third-party connected devices, whilst Apple disagreed that there was a different way of rendering access without the need to sacrifice end-to-end encryption).

Steer away: confusion and a dismembered business model

On our first DMA Agora instalment, I analysed the EC’s non-compliance decision fining Apple for its sub-par compliance solution relating to its compliance with the anti-steering prohibition under Article 5(4) DMA. On the same day that the newsletter’s edition was released, Apple announced new changes to its approach to compliance relating to anti-steering and app distribution. In terms of its distribution of apps (aka compliance with Article 6(4) DMA), Apple finally renounced its binary approach towards the DMA’s application.

The gatekeeper will no longer force developers to opt into the new developer business terms to enjoy the range of business opportunities presented by the DMA, as it did with its past approach. Starting in January 2026, Apple plans to move to a single business model in the EU for all developers, and it will finally drop the version of its services by which developers could still, for instance, be charged a 30% fee for the sale of digital goods and services. Apple’s legal representatives did not provide much detail since they still must tweak their approach to a single business model applying to all developers. Stakeholder participants voiced their concern about Apple’s changing approach to DMA compliance since it did not provide developers with enough time to adapt to the ‘deceased’ binary approach, as much as it will for the terms applying to the transition period between today and January 2026.

Furthermore, Apple has seemed to take action pursuant to the EC’s non-compliance decision relating to steering, since it has removed all restrictions relating to a developer’s capacity to link-out to a different website, app, or marketplace as well as to the in-app experience and integration, which will now allow users to perform purchases via web view, i.e., not requiring them to steer from the in-app experience. Developers will be able to use any number of URLs to link-out users outside of their apps, including parameters, redirects, and intermediate links. Those were formerly restricted by Apple, as set out in the non-compliance decision. In this same context, Apple has substantially tinkered with its disclosure sheet, shown to users before completing a transaction outside of the developer’s app, to the extent that users will be presented with a dialog enabling them to choose whether they wish to be presented with the disclosure once again in the future or not.

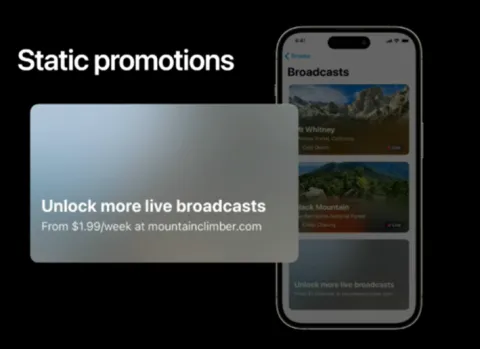

Pursuant to the ‘free of charge’ requirement contained in Article 5(4), Apple presented two technical changes to its approach towards steering meriting special attention. First, developers will pay nothing for static promotions on their app, as shown in the image below.

To the extent that the developer does not induce the user to link-out outside of its app to perform a transaction, Apple will not charge a fee for that particular aspect of steering. This rhymes well with the EC’s interpretation of the gratuity of steering, aside from the gatekeeper’s capacity to receive remuneration for its initial matchmaking role when a user downloads a third-party app as stemming from the value it generated through its app store.

Second, Apple has substantially reworked its approach to its fee structure, which will partially start to apply in January 2026. For instance, the fee that Apple charges to third-party developers operating alternative app marketplaces and sideloaded apps, the Core Technology Fee (CTF), will no longer be enforceable. Developers will not be charged 0,50€ per install performed on their apps and app marketplaces. Instead, Apple introduced three sets of fees a couple of days ago: the Initial Acquisition Fee, the Store Services Fee, and the Core Technology Commission.

The Initial Acquisition Fee applies within a 6-month period, ranging from the consumer’s download of the app and charges 2% on digital goods or services when users have used an actionable link from the developer’s app. According to Apple, the fee reflects the capabilities the App Store provides when connecting developers with customers in the EU. The fee only applies to new customers, counting since Apple announced the new fee structure. For those developers participating in the App Store Small Business Program, the gatekeeper has set the Initial Acquisition Fee at 0%. However, such a fee will only be charged in those cases where steering is de facto enabled for the particular developer, since Apple remarkably excludes them from combining the provision of alternative payment services with steering. This will entail that the Initial Acquisition Fee will be applied on top of its 3% IAP fee, accounting for Apple’s processing of payments. Asked by stakeholder participants, Apple’s legal representatives defended the bundling of IAP with steering responds to the need to ensure its App Store remains a trusted platform since it has already seen the deployment of manipulative mechanisms in the US as a result of the unbundling of both.

In the view of some workshop participants, the charging of the Initial Acquisition Fee represents a step too far, since the US Epic Games ruling on steering compels it to offer steering for free. The argument follows that a similar remedy could be applied as a compliance solution put forward by Apple with regard to the DMA. In Apple’s own words, we should “not be comparing apples to apples”, since both legal regimes differ in terms of their legal requirements and the way in which they are implemented.

The Store Services Fee is much more convoluted and difficult to grasp, since it accounts for Apple’s ongoing services and capabilities provided to developers via the App Store, including tools and technologies, app distribution and management, re-discovery, or promotional tools and services. Apple has divided the different tiers of the Store Services Fee into two groups: Tier 1 and Tier 2. Tier 1 accounts for the mandatory services provided by the App Store to all developers, priced at 5% of all sales on digital goods and services. Tier 2 includes these mandatory services and the optional services that developers may choose to enjoy in their apps via the App Store, such as particular engagement tools, access to app insights or marketing tools. The fee is priced at 13% for standard developers and 10% for those developers participating in the App Store Small Business Program.

Additionally, the Core Technology Commission (CTC) will apply to those developers who have already taken advantage of the DMA’s business opportunities by opting into the Alternative Terms Addendum for Apps in the EU, at 5% on all sales of digital goods or services that occur within a 12-month period from the date of an install, including app updates and reinstalls. In practice, this will mean that the CTC applies across an app’s or app marketplace’s lifecycle.

In the meantime (and until the ‘final’ new terms arrive in the iOS environment), a wide range of situations may arise in practice, where developers may be charged with the CTF whilst being subject to both the Store Services Fee and Initial Acquisition Fee and, even, developers are still charged at 30% on the sale of digitals goods and services until January 2026, without having received further notice on the upcoming changes.

What are we aiming at here?

DMA enforcement actions may get backtracked, if necessary. That was exactly what recently happened with Apple’s technical implementation of Article 6(3) DMA, and the EC’s non-compliance procedure against it. Despite initial allegations that Apple was not complying with the letter and the spirit of the law, the EC dropped the charges against Apple in April 2025. Since the triggering of the procedure, Apple updated its compliance plans twice (in August and October 2024) relating to the way in which it showed its choice screen to enable alternative browser engines to be set as a default on iOS.

In March 2024, Apple rolled out the choice screen for all its users (not only those with Safari as a default). The EC’s representatives also highlighted their concerns with the browser screen serving on a per-user basis, and not on a per-device basis. The nuance to the prompting towards the choice screen meant that users were only shown the choice screen once in the device’s lifetime, and those options were migrated to the new devices the users carried their information. Additionally, the EC held that Apple was administering unequal treatment to Safari vis-à-vis alternative browser engines since the user flow was different when Apple’s proprietary browser was set as a default as compared to the apps of alternative browser vendors.

In October 2024, Apple reemerged with a substantially different compliance plan by presenting updates to its choice screen, allowing easier and more neutral choices to be made. For instance, the same user flows are applied to the user’s choice, regardless of whether Safari was chosen or not. The choice screen would, in the future, only be displayed to users with Safari as their default (and not all users using the iOS) and per device. Moreover, Apple also went over and above and announced it would progressively make most of its native apps (such as Calls, Messages, or Photos) uninstallable from iOS and iPadOS. Similarly, developers were also given greater leeway when users exercised a choice in their favour. For instance, when a user selected an alternative browser, the app would automatically start downloading and appear on the screen when it was ready, without further clicks needed. Stemming from stakeholder feedback on their need to assess how they were doing as a consequence of Apple’s rolling out of its choice screen, the gatekeeper also introduced a dedicated API via its App Store Connect to enable them to access data about the performance of their browser on the choice screen, including selection rates, default selection and whether users had already viewed information on their App Store product page before they had chosen a given browser vendor’s app.

All these measures made Apple’s approach to Article 6(3) DMA good, but still, the gatekeeper remains unsatisfied with the results that the provision provokes in practice. Prior to the DMA’s application, Google Chrome held 55,3% of the market share on the mobile and tablet browser market share whereas Safari held 34,3% (and other browser vendors occupied the remaining 10,5%). According to the gatekeeper, one would have expected that the rest of the smaller browser vendors (e.g., DuckDuckGo, Ecosia, or Opera) would have ramped up in their market share since then. But this seems far away from the truth. Google Chrome not only remained in the market lead but increased its market share to 59,5% by biting off some of Safari’s apple, whilst the remaining vendors remained in approximately the same situation.

Apple’s legal representatives explained such a phenomenon as the unintended consequence of the EC’s regulatory dialogue. It was the regulator that pressed Apple to only roll out the choice screen when Safari was installed as a default on iOS and iPadOS (and, thus, no more choice screens were shown for users with a Chrome default), and, as such, Google Chrome thrives on the disparity. Additionally, as set out by a few participants representing competing web browsers, Google still prompts users through its suite of apps, such as Google Maps and Gmail, to make Google Chrome their default web browser (even on iOS devices). On this point, Apple cried for more parity in terms of the requirements imposed on each of the gatekeepers to comply with Article 6(3) DMA, which seem, in their own view, to be completely different at face value.

Finally, workshop participants enquired Apple further on its compliance with Article 6(3) on the topic of browser engines. That is, the engines powering web browser apps, which it had to open for other competitors and unbundle from its proprietary tool WebKit. According to Apple, it has done everything in its power to create the possibility for alternative browser engines to power browser apps on the iPhone. However, gatekeeper Alphabet and competitor Mozilla have not yet gotten to terms with them regarding the final integration and rolling out of such apps with their underlying technologies.

Against this framework, we cannot say that Apple hides anymore under the flag of privacy, security, safety, and integrity to hinder and undermine the DMA’s effectiveness but it isn’t out of the woods completely with regards to the core instrument designed by the regulation to enable alternative app distribution in line with the necessary introduction of fair-er terms imposed on third-party app developers (aka Article 6(4) DMA).

___

This is a re-post of the original piece published on The DMA Agora.

You may also like