Quality at the EPO – One Modest and one Serious Proposal

February 14, 2023

In the spirit of Jonathan Swift’s unforgettable Modest Proposal for preventing the Children of Poor People from being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country and for making them beneficial to the Publick,

Let us first consider a Modest Proposal of how the European Patent Office could be restructured to achieve

• 100% EPO Quality (which substantially means timeliness and process efficiency),

• 100% Applicant Satisfaction,

• an enormously faster speed of the examination proceedings,

• diligent use of modern technology, perhaps even AI,

• fantastic and unheard-of cost savings, which might justify a significant extra premium for the EPO Upper Management; and last but not least

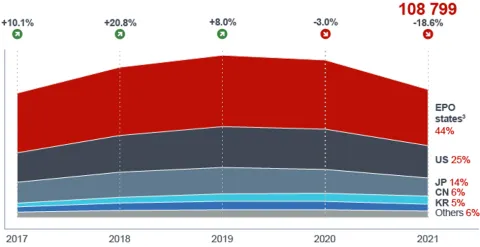

• higher satisfaction of the Delegates of the Administrative Council, who have recently displayed concerns about figures as shown in the following graph (decreasing number of granted patents per year), signifying less fees for the National Patent Offices.

Source: EPO

How to accomplish all of this with one simple change? Very easy:

Just stop search and examination, simply register all applications for grant and leave any disputes to the Opposition Divisions, Boards of Appeal and the Courts.

What a Brave New World this would be! The EPO finally at 100% efficiency. Much more money available for the EPO to be put into the stock exchange or into important exchange programs with National Patent Offices. Applicants 100% happy, because they finally get a patent for each of their applications and save costs for examination. EPO Upper Management almost certain to be highly rewarded for using the efficiency gains enabled by modern technology. The City of Munich will get back valuable and now superfluous office space. EPO Member States will earn fantastic validation fees every year. Delegates of the AC will no longer have to look at sad statistics such as the above. No more complaints to the Administrative Tribunal of the ILO. And no worries for the examiners, there will be plenty of well-paid jobs in private IP practice.

Okay, there may be a few companies here or there that could complain about just one minor aspect of quality of the new EP patents, i.e. substantive quality. But those companies are complaining anyhow, as Mr. President rightly noted recently:

“As a public service organisation we can expect negative feedback from time to time, as well as the positive. But for us to identify legitimate opportunities for improvement – and act upon them – we need feedback that is constructive and criticism that is grounded in fact and evidence”.

Therefore, nothing of importance seems to speak against my Modest Proposal and I just hope that I get a small percentage of the EPO savings once it has been implemented.

(Ok, just kidding...)

---

On a more serious note, you may perhaps wonder why there are nonetheless so many substantive examiners at the EPO and why I and many others are generally so supportive of them. Let me explain this.

The reason is the fundamental raison d’etre of the patent system, i.e. the idea that (human) inventors who have enriched the public with an invention that is novel, useful and inventive, should be rewarded with a temporary exclusive right, i.e. a patent. This helps to stimulate competition for the best ideas and to foster technological progress.

However, this concept requires an efficient filter mechanism that weeds out alleged inventions that are not novel, useful (industrially applicable) and inventive or that have not been described in a way that skilled persons can reproduce them.

Of course, you can leave everything to Opposition Divisions, Boards of Appeal and/or Courts, but you should also consider the less desirable consequences. First and foremost, you will need many more of these Divisions, Boards and Judges than you do now. Secondly, contentious proceedings before each of these bodies take a considerable amount of time and are expensive, particularly in Europe where you may have two instances before the EPO, followed by another two before national courts until the question of validity is finally settled. (Is there no room for some simplification and efficiency gains here? But this is for another post). Not every small or medium enterprise, let alone every single inventor, can afford such disputes. It is thus in the interest of a democratic society that awards equal rights to everyone (and every company) to provide, as a public service, an effective filter that separates the good from the bad inventions and provides for a reasonable certainty that the rights eventually awarded to patentees are good and valid.

The Court of Justice of the European Union recently held in C-44/21, paragraph 41 that:

In that context, it must be borne in mind that filed European patents enjoy a presumption of validity from the date of publication of their grant. Thus, as from that date, those patents enjoy the full scope of the protection guaranteed, inter alia, by Directive 2004/48 (see, by analogy, judgment of 30 January 2020, Generics (UK) and Others, C 307/18, EU:C:2020:52, paragraph 48).

Whatever one may otherwise think about this decision of the Court of Justice, this is the current standard, at least within the EU. Consequently, I think that the EPO should justify this presumption of validity by a reasonably rigorous examination of all patent applications on the merits before grant. You may now ask: But is the EPO not doing precisely this? Does the EPO in its current setup not provide such an “effective filter”?

The Industry Patent Quality Charter (IPQC) seems to think that it does not, at least that there is room for improvement, as it has been reported here and in other forums. I fully agree and may remind readers that similar concerns were expressed by about a dozen of renowned patent law firms in an open letter around 5 years ago. This letter led to one meeting with the EPO President as reported here in which the start of a “constructive dialogue” was envisaged by the EPO. I happen to be a member of one of the undersigning patent law firms. To the best of my knowledge, this “constructive dialogue” began and ended with this one meeting. Nothing further happened, at least no dialogue on this level.

If anything, it appears that the quality of EPO patents has further deteriorated since then. This can be concluded from one interesting set of figures that the IPQC presented to the EPO, i.e. the grant rate and the revocation rate following appeal over time, which is shown here:

Comparing 2015 to 2021, it seems that the EPO grant rate has increased from 61.5% to more than 70%. This looks great for patentees, but suggests that the filter function of EPO examination has slowly degraded. This conclusion is further corroborated by the amazing increase of the revocation rates following opposition appeal proceedings. As many as 46% of those patents that have been granted and opposed are now revoked by a Board of Appeal. In the “good old times”, the outcome of opposition and appeal proceedings was about a 1/3 mix in the first instance and 41% revocation on appeal.

These are the facts, and the EPO should not continue to ignore them and/or stonewall the messengers. Indeed, all the available facts and evidence clearly point to quality deficiencies in examination and, above all, searches. In the vast majority of cases, patents are later revoked because of state of the art that could and should have been found by the EPO but was not. The classic case is patent literature from same IPC class as the opposed patent, or even earlier patents by the same applicant. The EPO has or can easily procure detailed evidence to this effect by just analyzing Board of Appeal decisions and the prior art cited therein that resulted in the revocation of the patent.

Thus, search quality certainly can and should be improved. It should go without saying that examiners should not stop searching once they have found (or shown by the EPO IT support tools) one X document against claim 1 and a couple of A documents against all other claims. They should look into the subject-matter of all claims and thoroughly search for prior art of relevance thereto. They should be encouraged and enabled to also look at the examples and discouraged from providing an incomplete search by ignoring claim elements that they think are not patentable, e.g. because they are non-technical. Quite clearly, search examiners should be allocated sufficient time to perform a thorough search in each case. They should not be penalized for insufficient output if they need a couple of days or even a week or more for a complex application with 100 claims. Good quality needs time, and better quality needs more time!

The same is of course true for examination. Examiners should be encouraged to be thorough, not fast. Alas, the current trend seems to go into exactly the opposite direction. As one of the clearly knowledgeable commentators under the Kluwer Patent Blogger’s recent post on this subject rightly remarked (please read them in full!):

Maybe the IPQC would be interested to know that the pressure to reach more than 53K R71(3) communications before the end of May has gotten so high on line managers that they now routinely resort to instructing examiners not to spend more than a certain amount of hours on a search or examination action. Individual production is monitored on a bi-weekly basis at least. Time off work is discouraged. In the last weeks examiners are being put under immense pressure to grant everything they can and put non-grants on hold in order to “overachieve“ the COO’s instructions. Team Managers are clearly incentivised to reach these targets as their bonuses and grade and career advancements are made contingent on these being attained.In the most complex technical fields that routinely took 2.6 days per product (that’s the internal language for a final action in search or examination) in the last few years, it has been decided by management that they cannot be more than twice as slow as the fastest technical fields that currently require 1.1 days per product on average. In 2023 no team is allowed to be slower than 2.2 days per product. How an increase of 20% in speed for large swathes of the office (mainly in CII!) can lead to an increase in quality baffles the mind.

Above average is the new normal.

Examiners are being pressured to ignore non-important aspects such as non-essential clarity (whatever that is) or minor Art 123(2) objections (the applicant is responsible for the text) in order to further speed up the process.

And the other one:

In the early days of the EPO, the search was comprehensive and the examination as well. There was no piecemeal approach. Examiners had time to do their work properly. Nowadays quality at the EPO resumes itself to timeliness.

The EPO indeed still seems to use a definition of quality that includes timeliness. I have criticized this for years and wrote a long post about the EPO’s quality problems on this blog in 2018. Unfortunately, these comments have not aged at all. They are at least as relevant as they were in 2018, and if I am allowed to make one serious proposal to the EPO, then it would be to take the recommendations by the IPQC and in my posts to heart and implement them.

The incentive system of examiners might also deserve a fresh consideration. Until about five years ago, examiners used to receive two points for a rejection of an application and one for a grant. This was then changed to one point for each of these decisions, yet a rejection causes about twice as much work. Guess what happened in the years following this change?

While I am not aware that issues like this are currently seriously discussed within the EPO, we instead observe an abundance of “quality lyrics”, i.e. a collection of propaganda, self-praise and hollow promises, which would deserve a post of its own. What the authors of such quality lyrics seem to be unaware of, though, is a fundamental law, namely the law of conservation of quality (Qualitätserhaltungssatz). In its shortest form, this law goes like this:

The sum of actual quality and propagandized quality is a constant.

You may also like

Patent robot

I would abolish the maintenance fees before grant and compensate them with higher designation fees proportional to the number of designated states. I also would deduct (one or) two points of the examiner if a patent is (partially) revoked after opposition/appeal proceedings.