Patent Term Extensions in the Eurasian Region. Part 1

January 16, 2026

In this post, we have mined the Russian patent register for PTE records and processed the data into practical facts and figures.

Launch and Major Reform

The modern PTE system of Russia was launched on March 11, 2003. A patent relating to eligible subject matter could enjoy up to 5 additional years of existence. No supplementary patent certificates (SPC) were granted, but instead, certain claims were extended entirely.

Since January 1, 2015, PTEs have been granted as SPCs which contain a new set of claims relating to the product for which the 1st marketing authorization (1MA) has been granted. The new set of claims must be narrowed so that they are as close as possible to the authorized product and not go beyond the originally granted scope.

Below, the above-mentioned two legal regimes will be referred to as “old” and “new”.

Secondary laws further shaped the PTE system. The old system was governed by:

- Procedure No. 55 (effective from 2003 to 2009), and

- Regulation No. 322 (effective from 2009 to 2016).

Only the latter firstly directly enacted the list of PTE-eligible subject matter: a compound, or a group of, and a composition. This limitation was transferred to the new system’s secondary law:

- Procedure No. 809 (effective from 2016).

Figures

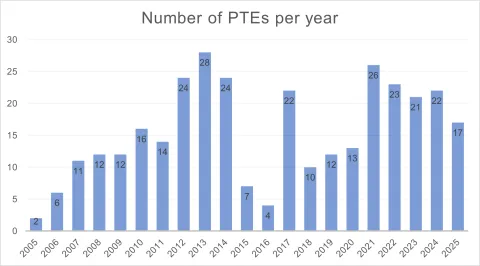

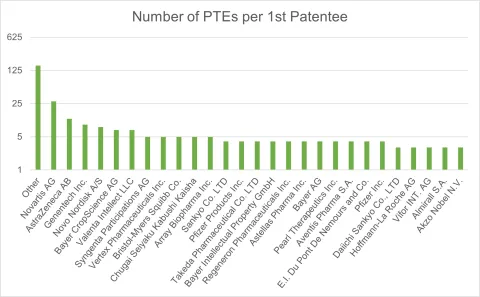

For years 2003-2025, we have identified a total of 326 PTEs, among which 158 are old PTEs; with the total number of PTE-ed patents of 318, including those originating from partial invalidation. Eleven PTEs have so far been invalidated directly or as a result of invalidation of their base patents.

The majority of PTEs relate to medicaments (296), with the remainder shared by pesticides (26), agrochemicals (2), and veterinary drugs (2).

Eligible Subject Matter

Currently, there is a two-step filter:

· the invention per se must relate to a medicament, pesticide, or agrochemical;

· the patent’s claims must contain eligible subject matter.

The first step is transparent because the relevant terms have statutory definitions (Art. 4 of the Law “On Circulation of Drugs”; Art. 1 of the Law “On the Safe Handling of Pesticides and Agrochemicals”).

The methodology for checking for eligible subject matter has evolved into its modern form under the new regime. The old regime seems to be more flexible.

Law scholars and practitioners admit that the current secondary law is limitative and suggest that it could be amended to explicitly incorporate other relevant subject matters. We believe this to be a pragmatic view. It is the scope of legal protection, rather than the category of subject matter, that should serve as a basis for deciding whether a patent relates to an eligible product.

Nevertheless, the new regime may potentially fall out of alignment, as can be seen below.

Common

· Composition and Compound

These are the most commonly PTE-ed subject matters since they directly characterize a medicament and an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

Compositions (261 PTEs) include both form-unlimited (“composition”, “formulation”) and form-limited (“tablet”, “solution”, “cosuspension”) matter. “Combinations” are also included, though they sometimes may have a broader meaning (see below).

Compounds (194 PTEs) can broadly be understood as including small molecules, including crystalline forms, salts, solvates; polymers, and biologicals, including macromolecules, such as antibodies, multimeric molecules, ADCs, vectors, viruses, and more.

· Use

Use-type claims abound among those PTE-ed too. Use claims may appear in the prescribed format (“A use of … as ...”; 65 PTEs), which is useful for patenting per se known products, as well as in formats that mimic product claims and usually originate from nationalized foreign applications, such as EPC2000-type claims.

The eligible use-type claim must relate to a product. Exotic use-of-a-method claims cannot be PTE-ed, at least under the current legal regime.

PTE-ed use-of-a-product claims may have different formulations, e.g., “use in medicine”, “use for the treatment of”, or “use for preparing a medicament for the treatment of”.

Less common

The following less obvious subject matters present in smaller numbers among the PTE-ed patents.

· “Kit”, “Product”, “Article”

These subject matters chiefly characterize a (packaged) pharmaceutical product, which includes one or more dosage units and may also include a leaflet and, according to one case, syringes. Examples of such patents include: 2320331, 2353412, 2384344, 2426554, 2438705, 2471483, 2519562, 2682671, 2687551, 2824998, and 2573830.

· “Combination”

This subject matter may be viewed as an extended and somewhat vague version of “composition”, and may relate to a product comprising two or more APIs allocated to separate units to be taken together or separately (e.g., 2404771, 2471483).

· “Device”

Only one patent—2608713—was PTE-ed with respect to, namely, “a multidose dry powder inhaler device”. This is a remarkable example, because devices have never been eligible for PTE, and can only be explained by that the device, prefilled with the composition, was regarded to be a “product” (see above).

Currently ineligible

We identified three old PTEs relating to “method-of-treatment” claims: 2054180 (Zhirnov), 2200158 (G.D. Searle & Co.), 2244709 (Novartis AG).

Duration of the Procedure

Old Regime

There is no information in the register on PTE application processing times, except for a single case (2177944), in which the PTE was recorded in the register 81 days after the patentee’s request. In general, the procedure was clearly fast, as there was no need to prepare amended claims and the examiner’s response time was limited (initially, 1 month, and 2 months from 2008).

New Regime

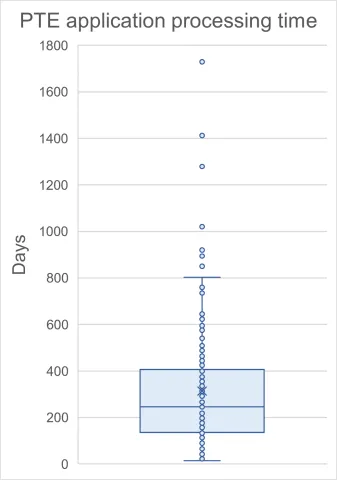

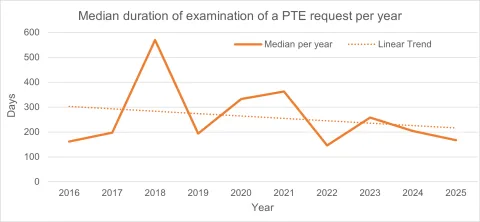

Thanks to the recorded dates of patentees’ requests, actual processing times can be observed, ranging from 14 days (2764750, Astellas Pharma Inc.) to 1,729 days (2361593, Cipla LTD) (~0.5 months to 7.4 years), with a median of 246 days (~8 months).

These figures [B1] [GS2] reflect the obvious need for coordinated efforts by the patentee and the examiner to develop a properly narrowed set of claims.

While there is no clear explanation for the outliers exceeding ~800 days (over 2 years), such durations may raise concerns, as they are comparable—or even exceed—the average examination time for a regular patent application.

In general, the duration of the procedure tends to decrease over the years.

Possible Combinations

One Patent, Multiple MAs

This option is indeed on the table and is increasingly used. For example, Pearl Therapeutics’ patent 2580315 was PTE-ed three times, each time based on a different drug. Daiichi Sankyo’s patent 2683780 was PTE-ed twice based on the same drug, with the 2nd PTE granted on the basis of a newly approved indication. In total, there are 7 multiply PTE-ed patents.

One MA, Multiple Patents

This option is less surprising, as a marketed product may embody multiple inventions at once (API, formulation, second medical indication), and, conversely, every successful original patent typically has a trail of secondary patents. Examples include Pearl’s patents 2586297, 2580315, which were PTE-ed based on Breztri Aerosphere, and Novartis’ patents 2493844, 2334513, PTE-ed based on Entresto, among many others.

Divisional Applications

Among the PTE-ed patents, 27 were granted on divisional applications. There is nothing special about this, because each patent—including one granted on a divisional application—is to be PTE-ed separately. However, the divisional route may be harnessed to bypass the 6-month deadline for applying for a PTE, as demonstrated by the highly controversial case of AstraZeneca’s Forxiga patent 2746132 (still valid).

Invalidation

PTE Invalidation

The validity of a PTE may be challenged on grounds common to patents in general (among others, non-compliance with patentability criteria, or added matter) as well as on special grounds specific to PTEs, namely the compliance with MA requirements, the scope of the narrowed claims, calculation of the extended term, and the deadline for filing a request.

Until 2022, PTEs had to be challenged directly in court within a very short deadline of 3 months. There are examples of successful PTE invalidations, such as Syngenta’s 2127265, Aventis’ 2481827, and Bayer’s 2319693 (partially).

In 2022, the special grounds for PTE invalidation were explicitly incorporated into the Civil Code. Since then, the following PTEs have been invalidated: 2283840, 2297415, 2438705 (all partially), and 2687551.

Base Patent Invalidation

When a patent is invalidated, the rights to it and to its SPC terminate. If a patent is partially invalidated, a new patent is issued and, normally, a new PTE request should be filed within 6 months, provided that the new patent still encompasses the registered product.

In practice, the following scenarios have occurred:

- 2177944 (invalidated) and 2595250 (new): the same initial PTE request was used to extend both patents;

- 2174977 (invalidated) and 2694252: separate PTE requests were filed;

- 2297415 was partially invalidated after the extended term had expired; therefore, no new patent was granted.

As follows from the PTE records, partial invalidation may theoretically be harnessed to “reinstate” a missed 6-month deadline for applying for PTE (e.g., 2458932, 2481827).

Wrapping Up

Since its inception, the PTE registration system in Russia has undergone numerous adjustments, and the nature of these changes reflects a search for the proverbial balance between patentees and competitors/society. While there is still room for improvement compared to older Western patent systems, this practical overview of the registry shows that the PTE system has acquired a predictable and mutually beneficial framework, including the duration and the permitted subject matter (not without anecdotal exceptions, of course). This is all taking place in the face of competition from the Eurasian Patent System, which is "pulling" patents in this niche. The regularity of legislative changes is good news: in the coming years, we will likely see further improvements, such as the elimination of the loopholes mentioned above, and perhaps even more fundamental issues, such as the interpretation of the 1MA. In this respect, all eyes should be on court practice for it is the main initiator of change.

You may also like