Breaking news: Referral on claim interpretation at the EPO

July 2, 2024

Following months of speculation, EPO Board of Appeal 3.2.01 yesterday issued decision T 439/22 referring questions to the Enlarged Board of Appeal on the extent to which the description and drawings should be used in claim interpretation.

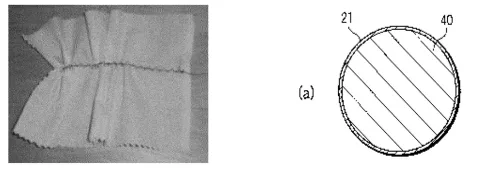

The claim feature at issue was: “in which the aerosol-forming substrate comprises a gathered sheet”. The key question in this opposition case is whether the claim feature “gathered” should be interpreted narrowly as a complex 3D structure in line with the left hand side illustration below, based on the clear common general knowledge. The opponent contests this and argues that a broader express definition given in the patent should be adopted which covers a sheet formed into a cylinder in line with the right hand side illustration from the prior art below.

The following questions were referred:

- Is Article 69 (1), second sentence EPC and Article 1 of the Protocol on the Interpretation of Article 69 EPC to be applied to the interpretation of patent claims when assessing the patentability of an invention under Articles 52 to 57 EPC? [see points 3.2, 4.2 and 6.1]

- May the description and figures be consulted when interpreting the claims to assess patentability and, if so, may this be done generally or only if the person skilled in the art finds a claim to be unclear or ambiguous when read in isolation? [see points 3.3, 4.3 and 6.2]

- May a definition or similar information on a term used in the claims which is explicitly given in the description be disregarded when interpreting the claims to assess patentability and, if so, under what conditions? [see points 3.4, 4.4 and 6.3]

There has long been a tension between the two main EPO approaches to claim interpretation:

- The “own dictionary” approach, in which terms in the claims can be defined in the application; and

- The “primacy of the claims” approach, in which clear terms in the claims are interpreted by the skilled person without the aid of the description.

Attempts have been made to reconcile these approaches by holding that the “own dictionary” approach only applies where the relevant term in the claims is unclear, and that limitations cannot be read into the claims from the description. At the same time, EPO case law also holds that claims should be interpreted based on the whole disclosure of the patent with a mind willing to understand, and that the “broadest technically sensible meaning” should be adopted. With so many, often conflicting approaches, it is no wonder that a lack of legal certainty remains.

The lack of agreement between the Boards on the legislative basis for claim interpretation for substantive patentability exacerbates this uncertainty. Recently, T 1473/19 opted for Article 69 EPC and T 169/20 relied instead on Article 84 EPC. It is safe to say that neither article gives clear support for the “primacy of the claims” approach favoured by these Boards. Article 84 doesn’t even expressly mention claim interpretation, while Article 69 if anything states that “the description and drawings shall be used to interpret the claims”. The situation is even more complex when the approaches of the national courts are taken into account, as they tend to favour the “own dictionary” approach.

T 439/22 outlines three main points on which the Board considers there to be divergence at reason 3.1:

- legal basis for construing patent claims

- whether it is a prerequisite for taking the figures and description into account when construing a patent claim that the claim wording when read in isolation be found to be unclear or ambiguous

- extent to which a patent can serve as its own dictionary

The decision then discusses the various approaches of previous Boards supporting this finding of divergence. Underlining the point we made above about the difficulty of finding a consistent rule on this issue, a large number of decisions and legal rationales were cited.

Reason 4 of the decision explains why this is a point of fundamental importance. Several national decisions, as well as the UPC CoA decision in Nanostring v 10x Genomics were cited. In our view, claim interpretation is such a central issue for so many aspects of patent law, that it is hard to dispute the fundamental nature of the referral.

While we welcome this brave move to question the status quo by Board 3.2.01, we can't help but fear that the desired legal clarity may not actually be achieved with this case. As the difficulties on finding a compromise on Article 69 EPC over the last few decades show, finding a golden rule defining a fair balance between the claims and the description is difficult.

As Bob Dylan put it in “All along the watchtower”:

There must be some kind of way outta here

Said the joker to the thief

There's too much confusion

I can't get no relief

We therefore welcome the decision to refer, in the hope that this will lead to improved legal certainty and some long overdue relief.

You may also like

DXThomas

The decision has been commented in another blog. The question of application of Art 69 and Art 1 of the Protocol in procedures before the EPO has been lingering for a while, and it is good that a board has now decided to refer this important question. It is to be noted, that the analysis of the diverging case law by the referring board is quite impressive and actually shows the necessity of such a referral. The referral has been limited to the application of Arti 69 (1) and Art 1 of the Protocol on Interpretation, when a claim has to be assessed with respect to Art 52-57. The board did not bring in Art 123(2). This position differs from that adopted in T 450/20, and T 1473/19, In T 450/20, the board refused to refer questions about the application of art 69 and its Protocol to the EBA. Although the boards in T 450/20 and T 1473/19 considered, the primacy of the claims, they considered that Art 69 its Protocol should also be applied when assessing added matter. It is to be hoped that the EBA does not start rewriting the questions in order to answer questions which have not been referred to it. The referring board related its questions to Art 52-57, but, for apparently good reasons, did not mention Art 123(2). In this respect a “disclaimer” on Art 54(1 to 3) could appear appropriate in order not to jeopardise the “gold standard”.

Further Processing

This is a fundamental question indeed. But in my opinion, there is a rather simple solution. The clarity of the claims and the consistency between claims and description is solely within the control of the applicant/patentee. Hence, any lack of clarity must be construed against the patentee. In questions of patentability, the broadest technically sensible meaning must include any broader meaning assigned to a claim term by a definition in the description. In questions of infringement, a more narrow definition of a claim term in the description must be applied, already for ascertaining legal certainty for the public. With this principle, the applicant/patentee is prevented from achieving an unfair advantage arising from lack of clarity or inconsistency between claims and description.