Copyright Infringements in Output of Generative AI: Who is liable for infringing reproductions?

November 17, 2025

This article is an adapted and shortened English version of the German language article „Haftung für Urheberrechtsverletzungen im Output generativer KI-Systeme“, published in Gewerblicher Rechtsschutz und Urheberrecht (GRUR) 2025, 955. The (full length)-English version has been prepared together with Adam Ailsby, Belfast, https://www.ailsby.com/. For the full length-English version see https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5721084

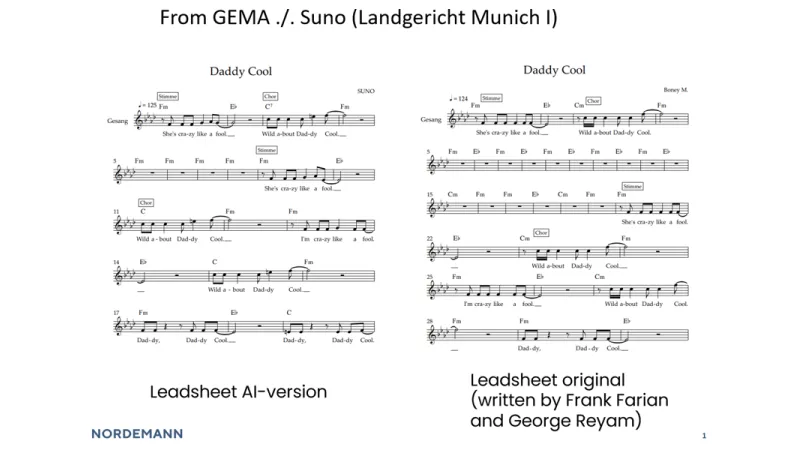

Copyright and AI are everywhere these days. But it’s not just about whether copyrighted works are being used to train generative AI models (as many might assume). There are plenty of other copyright questions that come up as well. One that is often mentioned but rarely explored is this: if AI-generated content is copyright infringing, like the German collective management organization GEMA argues in its (pending) case against SUNO before the German Landgericht (Regional Court) Munich I for example for the song “Daddy Cool” (written by Frank Farian und George Reyam, see picture of a comparison of the lead sheets for the original and the AI version generated as an output on SUNO), who is actually liable for copyright infringing output? In the other GEMA case against Open AI already decided by the Regional Court Munich, the Court argued that OpenAI was primarily liable as the reproducer of infringing lyrics in the ChatGPT output. This article explores this question in relation to an infringement of the reproduction right pursuant to Article 2 of Directive 2001/29/EC (InfoSoc Directive).

To determine liability, several preliminary questions must first be clarified. This will involve devising infringement scenarios and identifying potentially liable parties. A set of criteria for attributing liability then needs to be developed.

There are a variety of potential causes of copyright infringement in the output of generative AI systems. These causes can be assigned to different participants based on varying risk and causation spheres. One possibility is that infringing copyright is inherent in the target function, meaning the intended purpose of the generative AI system, without the infringed work having been used to train the AI. Besides this, however, AI-generated copyright infringements can also have other system-based causes. The risk is particularly high where the AI system becomes too closely aligned with the training data used. Lastly, copyright infringements could also be conjured forth as a result of user prompts at the usage stage. This could be, among other things, following intense drilling down into generative AI models looking for works used for training. In all these cases, either the user of an AI system or its provider (Article 3, point (3) of the AI Act) could be liable for the generated copyright infringement.

When AI systems generate copyright infringing output, the first look will go to an infringement of the right of reproduction, as set out in EU law under Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive, arising from a user’s request for output.

In its rulings in “VCAST” and “Ocilion”, the CJEU created a system for (directly) attributing acts of reproduction to a specific party to determine if the reproduction may benefit from the private copying exception. According to the CJEU, it is crucial to determine whether a given party merely assumes the role of a copying service provider for a third party’s acts of reproduction or whether the act of use in question is directly attributable to that party as its own act of reproduction. The determination in this regard rests primarily on whether the party concerned actively involves itself in the act of reproduction. A conclusion of active involvement depends on a variety of factors.

These criteria should also be applied in the context of the output of generative AI systems to find primary or secondary liability for the infringing AI output.

Alongside this, the CJEU has also created a liability regime under EU law specifically for the exploitation right of communication to the public. Within this liability regime, Article 3 of the InfoSoc Directive also acts as a liability provision. In the event of a violation of the right of communication to the public, the CJEU assumes, under certain conditions, additional (secondary) liability for parties that indirectly cause the infringement (in addition to the perpetrators who are directly responsible). The first condition is that such indirect perpetrators have played an “indispensable role” when their users make potentially illegal content available. This requires there to be a sufficient degree of influence over the direct infringer or at least risk-enhancing conduct on the part of the intermediary. The second condition is that the indirect perpetrator must have breached certain duties of care.

When evaluating the liability regimes, there are several arguments in favour of applying the secondary liability regime developed by the CJEU in the context of the right of communication to the public, which allows for flexible attribution of liability, to the right of reproduction and thus also to the production of copyright-infringing output by generative AI systems.

That said, it is necessary to combine such a secondary liability regime (for indirect contributions) with the regime for finding (attributing) direct acts of reproduction established by the CJEU in “VCAST” and “Ocilion” to form a coherent overall system.

When applying this liability regime to the generation of copyright infringing AI output, the first question that arises is which of the parties involved is primarily liable for copyright infringements caused by user input:

· Users are directly involved in the production of copyright-infringing output if the AI output is based significantly and purposefully on user input. Since the infringement is caused directly by the user input, this seems to be the case. Therefore, responsibility can be attributed to the user based on CJEU rulings in 'VCast' and 'Ocilion'. The user actively intervenes in the creation of the reproduction. Consequently, they are primarily liable (as direct infringers or perpetrators) for the copyright infringement they have produced themselves.

· For secondary liability to apply, AI providers must first play an indispensable role in users' copyright infringements. However, this seems doubtful for the type of case being discussed. This is because the infringement essentially stems from user input and AI providers and developers cannot exert any control over it by setting the intended purpose or training the AI system. In such scenarios, therefore, we would rule out secondary liability due to the AI system provider's lack of an indispensable role.

Cases in which a copyright infringement is not primarily attributable to user input but instead has system-based causes will have to be assessed differently. One must consider whether the generated output is identical to the works used for the training:

· In these cases, the direct act of reproduction could be attributed to the provider of the AI system, because the copyright infringement is a manifestation of systemic risks. The key factor is who has primary control over the determination of the composition of the rights-infringing output. Such control will lead to primary liability for the provider of the AI system. Where the prompts are brief and worded openly but defects in the training lead to rights-infringing output, the act of reproduction must directly be attributed to the AI provider.

· However, there are cases that must be evaluated differently. Even where AI providers do not reproduce directly, secondary liability also may be possible. For this, it must be shown that the AI provider breached a duty of care. To ascertain what this might look like, one possibility would be to look at the system of obligations developed by the CJEU for platforms and file-hosting services, such as the YouTube/Cyando case.

· In this context, the AI provider would, e.g., breach a relevant duty of care if they know or ought to know that copyright-infringing output is being generated by users via the AI system and the provider does not put in place any appropriate technological measures, such as could reasonably be expected from a reasonably diligent economic actor in its situation, in order to credibly and effectively combat copyright infringements in the output of its AI system. In this light, it would be particularly important if the training were conducted in accordance with the current state of science and technology. This includes ensuring that the dataset used is sufficiently large, diverse and well-prepared. In particular, so-called canaries must be removed from the training data, i.e. works that appear multiple times in the dataset, which make the appearance of these works in the output more likely.

Finally, liability for copyright infringements in the output of generative AI systems could also be assigned, differently from the types of case already examined, if the copyright infringement is inherent in the intended purpose of the AI system.

· In this case, the user's selection of the infringing work suggests that they actively determine the AI output. Accordingly, the act of reproduction within the meaning of Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive would be directly attributable to the user.

· However, the AI provider could still be liable as a secondary infringer. The argument that the provider of an AI system plays an indispensable role, whose intended purpose enables copyright infringements, is supported by the fact that the provider is in a contractual relationship with the user who directly infringes copyright. This would enable the provider to prohibit the user’s rights-infringing use, at least contractually. It will, however, be necessary to assess the indispensable role individually for each specific case.

· Nevertheless, insofar as the AI provider cannot be held secondarily liable, they may be subject to injunctive relief under the principles of Art. 8 (3) InfoSoc Directive.