Copyright and AI policy in the UK in 2025

December 30, 2025

The UK did not implement the CDSM Directive with its two text and data mining (TDM) exceptions (Articles 3 and 4). Neither does the UK have any horizontal AI regulation such as the AI Act. Nonetheless, the UK has not remained isolated from the AI and copyright debates that dominated these two pieces of legislation. Neither has it become immune to these legal conundrums. The UK law and policy makers have a lot to figure out and are trying to do that on the back of the experience in other jurisdictions such as the EU.

This post recaps the present policy situation in the UK and walks readers through a timeline of what has happened in the UK in AI and copyright in 2025 and gives a brief snapshot of what to expect in 2026.

The UK provisions on copyright and AI

Presently, the only provision somewhat linked to the training of AI models is s29A of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA). It is relevant only to non-commercial research and was never designed with AI in mind. Furthermore, it has its own problems (see Kretschmer et al here). On the other hand, some have waved the computer-generated works protection in s9(3) CDPA as the solution to the output issues in AI-generated works. That one has its own issues too (see Goould here). In view of these somewhat limited legal provisions, law and policy makers have been pondering which direction to take when it comes to generative AI (genAI).

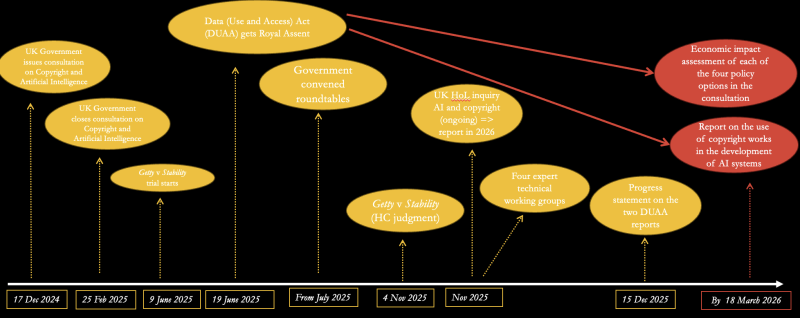

A timeline

In the beginning of 2025, the UKIPO closed its public consultation on copyright and AI, which provoked a serious outcry among the creative industry and the public (see here, here and here among others). This dissatisfaction was felt mostly during the last few days before the deadline for responses expires - if one were to approach any sort of public space on 25 February 2025 (the last day of the consultation), the message was: ‘MAKE IT FAIR: the government is siding with big tech over British creativity’. The number of responses received by the UKIPO is astronomical; more than 11, 000. The consultation questions were many and covered several different issues, but the most provocative debate is expected to be on the TDM copyright exception. The consultation suggests four potential solutions for commercial TDM, but champions one as the most appropriate one - a data mining exception which allows right holders to reserve their rights, underpinned by supporting measures on transparency. Those familiar with the EU debate will notice the resemblances to Article 4 CDSMD and Article 53(1)(c) and (d) AI Act.

Other aspects on which opinions were sought included the repealing of s9(3) CDPA on computer-generated works as well as potential protection of image rights. The UK does not have an unfair competition law, nor does it have any personality rights regime, but relies heavily on the doctrine of passing off when it comes to protecting one’s likeness.

In the meantime, the high-profile Getty Images v Stability AI trial took place from 9 June 2025 onwards. During the trail, the primary infringement claims were dropped partly due to a strong argument that since training of the model took place in the US, the UK courts’ jurisdiction would not have been clear (see Quintais and Derclaye on issues of extra-territoriality). On the copyright front, this left the court only with the claim for secondary infringement focussing on the argument that Stable Diffusion is an “infringing copy” as it has been imported in the UK. The case involved also a trade mark infringement and a passing of claim. The judgment was delivered eventually on 4 November 2025 and Getty lost the copyright battle (see here). In December 2025, it became clear that Getty has been granted permission to appeal.

In the meantime, the Data (Use and Access) Act 2025 got Royal Assent on 19 June 2025. This piece of legislation is not a copyright one, but includes three simple, but rather interesting provisions, which draw the debate on copyright and AI together. The first one promises the delivery of an economic impact assessment of each of the four policy options provided in the consultation (s135). The second equally promises a report on the use of copyright works in the development of AI systems (s136). The deadline for both is end of March 2026. Equally, by 19 December 2025 a progress statement is to be issued on the two promised reports (s137). The statement was issued on 15 December 2025.

From July 2025, the government started engaging more actively with representatives of the creative, media, and AI sectors and academia by virtue of convening roundtables. In addition, four expert technical working groups have been put together to look specifically at:

- Control and technical standards – meeting on 25 November 2025, the group is exploring “what makes technical tools and standards effective for controlling content use, their current limitations, and whether legislation or guidance is needed to drive adoption and compliance”;

- Information and transparency – meeting on 2 December 2025, this group is exploring “what legal transparency duties could include (e.g. training data summaries, crawler disclosures) to address concerns from the creative industries without being overly burdensome for AI developers, and how they could vary by actor type”;

- Licensing – meeting on 4 December 2025, this group is considering “the strengths and weaknesses of the current licensing framework, especially for smaller creators and is looking at potential ways to facilitate licensing”;

- Wider support for creatives – meeting on 24 November 2025, this group is considering additional protections for the creative industries.

It has been reported that 50 participants have taken part in the discussions across the four groups.

Furthermore, a cross-party Parliamentary working group has been convened. It appears that two meetings have taken place – one in October and a second one in November, providing an “open forum to discuss and update Parliamentarians on the government’s policy principles”.

In November 2025, the Digital and Communications committee of the House of Lords opened an in inquiry into copyright and AI, which includes several oral witness sessions as well as written submissions upon request. The committee’s report is expected to be issued some time in the beginning of 2026 and promises to look at various familiar themes such as licensing of copyright works for AI training, transparency mechanisms, as well as the current TDM.

Comment

The three provision in the Data (Use and Access) Act 2025 are rather unexciting on the substance side. They can certainly be seen as a roll back and a response to the concerns vocally raised by the creative industries in light of the proposed option for TDM.

Nonetheless, two things can be said about this entire law and policy making process. First, the UK can be congratulated for the high level of transperency in this complicated scenario. Every country is striving to strike the right balance between the intersts of everyone involved (the rightholders, the AI industry, the public, SMEs, etc), but unfortunately many of these debates, meetings and lobbying efforts remain unseen and unreported. This time, the process feels different. The progress statement published on 15 December 2025 very helpfully summarises the various initiatives and developments. This allows the wider public to genuinely appreciate not only the complexity of the status quo, but also to be part of the discussions.

Second, the UK is actively seeking to find sufficient and convincing evidence in order to legislate in the best possible direction. There is a real desire to consult experts, intersted parties and listen widely before any laws, hard or soft, are crafted. The end goal is a working and practically effective and fair legislation.

With such a variety of initatives that took place this year, 2026 certainly looks promising.

You may also like