The Roman Holiday of Denial of Access and the DMA’s Centralised Enforcement System

December 1, 2025

At the end of William Wyler’s Roman Holiday (1953), Gregory Peck leaves the Palazzo Colonna Gallery behind, symbolising the bittersweet end to his romance with Audrey Hepburn in the movie (apologies for the spoiler, though!). That scene is one to stick in one’s mind.

The Italian competition authority’s recent enforcement in digital markets introduces a similar spin to the theories of harm that we have seen competition authorities apply in the digital space. Following its landmark Android Auto case (Case C‑233/23, which basically merited the Court of Justice’s lowering of the legal standards for refusals to access, see here), the Italian competition authority has not grown shy from the challenges ahead of itself (and the European Commission) to tackle unfair practices implemented by both Meta with regards to how it integrates its Meta AI chatbot into WhatsApp (previously analysed by Todd Davies here) and Google’s technical implementation of the DMA obligation under Article 5(2) DMA.

This blog post analyses them in turn to convey the Italian competition authority’s covert impact on the DMA’s enforcement as it pressures gatekeepers to open their platforms in line with its consumer protection mandate and its expansive categorisation of denials of access in the digital space.

Is this the elevator? This is my ROOM!

The analysis of denials of access, at least in the digital space, will never be the same after the Court of Justice’s Android Auto ruling. By re-drafting the questions that the Italian judicial authorities directed at the CJEU, the legal test for finding an infringement in the shape of a refusal to access is much lower than it used to be. The Court of Justice produced two main findings that prove this distance. First, the requirement of indispensability was tempered down to require that the undertaking’s offerings should be ‘more attractive’ to consumers (para 36 of the ruling). Second, the refusal’s likely elimination of all competition in the market in question on the part of the entity requesting access was lowered to only require that the competition authority prove that competition was hindered as a result (para 61). The Court of Justice’s controversial ruling followed its extensive analysis of the facts of the case: Google developed Android Auto as an open platform and, therefore, it should abide by those same rules when assessing requests for access to its (non-)indispensable Android Auto infrastructure. In this sense, the strict Bronner (C-7/97) conditions did not apply to the case at hand because Google had not developed the infrastructure solely for the needs of its own business (para 40).

It follows, then, that open platforms must not hinder access to their infrastructure when their offerings appear ‘attractive’ for their competitors to depend on to operate in downstream markets. In other words, open digital platforms cannot suddenly decide that they prefer to close their infrastructure to a set of given economic operators, because competition authorities will interpret such a shift as bearing anti-competitive traits.

Against the background of the recent developments, the Italian competition authority’s decision to implement interim measures regarding its Meta AI case seems all the more relevant. Back in July, the Italian competition authority launched its investigation into Meta’s potential abuse of a dominant position due to its decision to pre-install its AI chatbot service on the WhatsApp app. According to the competition authority, Meta would be able to ‘force’ its users to use its chatbot and AI assistant’s services.

Initially, one would have thought that the Italian competition authority was pursuing a tying case. As Davies and Iskander already highlighted in a previous post, the self-preferencing category did not fit. However, Meta does not allow users to eliminate the AI chatbot from their WhatsApp app. Therefore, the logic of the case defies its categorisation as tying as it does not meet the requirement of it not being possible to obtain the tying product without the tied product. If one turns to the EC’s Facebook Marketplace decision, when the dominant undertaking’s services are exclusively available on its platform (to the exclusion of its competitors), this sense of compulsion or coercion can also be understood to be met. Tying it is, then!

Notwithstanding, the Italian competition authority demonstrated its courage once again on the 26th of November when it opened a procedure for the adoption of interim measures against Meta over its abuse of a dominant position. According to the decision (only available in Italian here), Meta modified the contractual conditions (the WhatsApp Business Solution Terms) in October, governing its business API policy to ban general-purpose chatbots from its platform. The shift does not touch upon those business customers that serve customers on WhatsApp by using AI, but rather to those competitors that act as a platform for chatbot distribution. Meta confirmed that it is banning chatbot use cases because they placed an increased message volume and required a different kind of support as a consequence of the integration of OpenAI’s launch of ChatGPT or Perplexity’s own bot on WhatsApp. Commentators pointed out that Meta’s decision followed its wish to monetise this segment of the market (chatbot distribution on WhatsApp) because it could not charge businesses by offering message templates like marketing, utility, authentication, and support services, as it does for other providers. The API design is simply not available on the service, so Meta cannot monetise via these means. These changes on WhatsApp’s Business Solution Terms kicked in for any operator wishing to seek access to WhatsApp’s Business API without a previous account. For those companies with an account, the ban will enter into force in January 2026.

Aside from the tying allegations of the AI chatbot with WhatsApp, now the case has turned a different colour with Meta’s new version of its WhatsApp Business Solution Terms. On the decision proposing the imposition of interim measures to stop the term’s implementation in the short term, the Italian competition authority replicates the terms of the CJEU’s Android Auto ruling by stating that Meta’s change of terms entails a “denial of access to a digital infrastructure from the beginning developed by the dominant undertaking not only for the needs of its own activities, but also with a view to allowing the use of that infrastructure by third-party undertakings”. As the decision points out, “since October 2025, the possibility for companies entering the AI chatbot services market has been precluded”. By implementing the ban, Meta “prevents other companies providing AI chatbot services to use the WhatsApp platform, thus preventing them from accessing the platform’s large user base”. On top of that, the Italian competition authority highlights that Meta will be able to gain a competitive advantage not only due to the direct impact of the denial of access (i.e., exclusion of competitors) but also to its indirect effects, given that Meta will be able to the only one to train its own AI chatbot with data from WhatsApp end user interactions via reinforcement learning of its AI model.

The Italian competition authority’s change of heart reinstates the rationale underlying Android Auto: once a dominant digital platform opens its services to downstream competitors, it cannot backpedal its decision by excluding them from those markets later. In this particular case, it goes a step further by expanding this line of reasoning to a constructive refusal to access. One could think, therefore, that dominant undertakings can operate more freely, without having to bear the scrutiny of competition law, if they develop and invest in their own infrastructures and clearly limit any access thereof. That is, however, completely contrary to the point (and the existence) of digital platforms, to the extent that they rely on different groups of users transacting on them to increase the platform’s overall value.

Let’s not forget that Meta’s WhatsApp is also a core platform service in the sense of the Digital Markets Act (DMA). Due to the application of the DMA, this particular case triggers a clear overlap with two distinct provisions: Articles 6(6) and 5(2) DMA. The latter, which prohibits the combinations of personal data across a gatekeeper’s CPS, crosscuts WhatsApp’s integration of its chatbot (as Meta already did with Facebook and Instagram), relating to how reinforcement learning of the underlying AI model will work. When WhatsApp users react to the answers provided by the Meta AI chatbot by providing it feedback embedded on its interface (via a thumbs up or down) or by responding to it with further prompts, personal data may be generated in the interaction. Assuming that Meta then combines and cross-uses that personal data for the further refinement of its AI chatbot (considered as a separate functionality within WhatsApp), Article 5(2) prohibits such processing activities. Most importantly, however, Article 6(6) DMA compels gatekeepers not to restrict technically the ability of end users to switch between different services that are accessed using the CPS. Meta’s decision to ban other chatbots from its WhatsApp service falls precisely under the scope of such a prohibition.

The Italian competition authority’s decision to reframe its own Article 102 TFEU case against Meta’s integration of its AI chatbot effectively acts as a back-door attempt to address the same type of conduct targeted by the DMA, at a time when the European Commission shows no intention of prioritising the matter under its own enforcement of the digital regulation. The situation is reminiscent of Audrey Hepburn’s Princess Ann asking Gregory Peck’s Joe Bradley whether the room she just entered is the elevator. The Italian competition authority enters the Article 102 TFEU room, only to realise that it is not a lift at all, but rather the European Commission’s DMA space and enforcement domain.

You spent the whole day doing things I’ve always wanted to

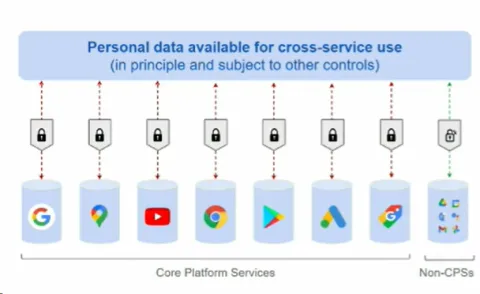

Back in March 2023, Google put forward its implementation of Article 5(2) DMA. The changes to its business model consisted of siloing its back-end infrastructure for each CPS (including the non-CPSs, which were also siloed as a consequence of the Bundeskartellamt’s intervention via Section 19a GWB, see here) so that no service combined or cross-used personal data without user consent.

Figure 1. Google's means of compliance with Article 5(2) DMA, as shown by the gatekeeper at its first compliance workshop.

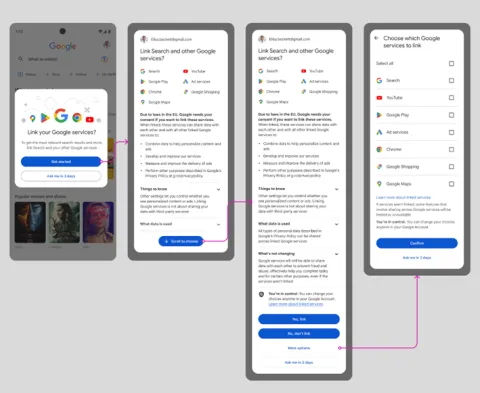

On the front-end, Google released four consent screens allowing end users to consent to data combinations and cross-uses of personal data across their CPSs. After a detailed examination of the data concerned by those combinations, the end user would have the option to select the CPSs for which they wished to open the gates for data combinations to take place. That particular choice (by ticking one or all the boxes in the prompt) would, in turn, unlock the silos within the back-end infrastructure.

Figure 2. Google's prompts in the form of their first iteration of the 2023 compliance reports.

Since 2023, Google has made minor non-substantive adjustments to its existing compliance measures relating to Article 5(2). For instance, the prompts now clarify that the display of personalised ads will also depend on the end users’ page and that linked services can share data with each other and all other linked Google services (despite that, in Germany, some services may not be combined as a consequence) (page 9 of Alphabet’s compliance report).

In July 2024, the Italian competition authority took issue with Google’s way of complying with Article 5(2) by applying its consumer protection mandate (and not the DMA, since NCAs only hold a supporting and secondary role with respect to its enforcement). The competition authority believes that the consent screens shown to Google users are; i) misleading, because they do not adequately inform consumer about the purpose and effects of consent, which Google services are linked if consent is given and the possibility of personalising consent; and ii) aggressive, to the extent that they unduly influence the average consumer to give his consent by blocking Google Search until a choice is made and overemphasising that, in case of refusing consent, some functionalities of the services that involve data sharing will be limited (while the impact of rejecting consent would only be potential or concern functionalities of the services that might not be of interest to the end users).

From an institutional perspective, the Italian competition authority’s action is completely justified, since Article 1(6) DMA perfectly accommodates this type of enforcement to take place in parallel to the regulation’s application. In practice, however, the NCA’s intervention prompts the idea that the DMA’s centralised enforcement system is not, in the end, going to hold its ground (as I demonstrate in my paper here). Bearing in mind that NCA’s dispute gatekeepers’ compliance solutions at the national level based on the legitimate exercise of their competences, it may well be the case that some Member States merit an enhanced DMA protection as opposed to others. This is, for instance, the case for Germany with respect to Google’s data combinations and cross-uses on its non-CPSs, which remain covered by the same type of prohibition. And it may well be the case that the same may happen with respect to the Italian competition authority’s actions.

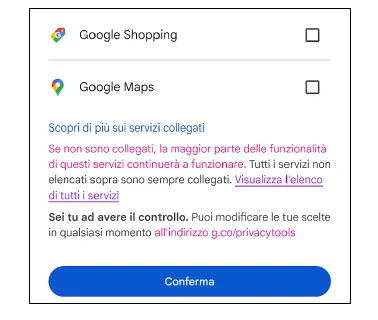

In the end, Google decided to propose commitments to the Italian NCA by clarifying all the aspects that the agency had disagreed with, notably the request’s inclusion of the object and effects of granting consent, the option to personalise consent, and the possibility of postponing the request. For instance, see below (in pink) Google’s inclusion of an additional sentence on the prompt detailing that if some services are not linked, most of their functionality will continue working.

Figure 3. A screenshot of Google's proposed commitments to the Italian competition authority.

The gatekeeper will implement the changes within a period of 6 months and inform Italian consumers via email of the transformation that the consent request has undergone. Google has reserved the right to change the consent request across the EEA to present it in a uniform and consistent manner.

In the end, it seems that the Italian competition authority’s covert pressure under the premise of consumer protection will impact all EU users and raise the effective enforcement threshold for complying with Article 5(2) DMA relating to Google’s services (and which may also indirectly touch upon the rest of the gatekeepers' approaches to complying with the prohibition). It would be only reasonable that if Google must amend its consent screen to meet consumer protection standards (incidentally concerned under the DMA’s own anti-circumvention clause), then the European Commission can ask the rest of the gatekeepers to follow suit.

The European Commission is already outsourcing some of the enforcement work that it cannot handle itself by issuing memoranda of understanding with NCAs to establish joint investigative teams that the NCAs fund with their own resources (examples include the Spanish, Dutch, Italian, and Luxembourg). For instance, when it launched its market investigation on the DMA’s application to cloud markets, the enforcer already recognised that it was being supported by the Dutch competition authority, in the form of a joint investigative team (building on its previous experience as derived from its market study on cloud services issued in 2022). The NCA’s enforcement of Article 102 TFEU and their own national laws against the gatekeepers is a distinct form of such an outsourcing, where NCAs, as Princess Ann recognises, spend the whole day doing things (the European Commission) always wanted to. Both cases signal that the DMA is not just a bilateral effort that the European Commission must overcome, but rather a fight inflicting several cuts on the gatekeepers (and seeing whether any of those fly, institutionally and theoretically, with the national and EU courts).