Meta’s Second DMA Compliance Workshop: A Half-an-Egg Omelette

July 18, 2025

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) became entirely applicable on 7 March 2024 for most gatekeepers. By then, the gatekeepers issued their compliance reports documenting their technical solutions and implementation of the DMA’s provisions under Article 11 DMA, as well as their reports on consumer profiling techniques as required under Article 15 DMA. A year later, six gatekeepers submitted an update to the first version of their compliance reports (they can be found here).

This is the last edition of this year’s compliance workshops held by the European Commission, addressing Meta’s face-to-face with stakeholders in discussing their compliance plans surrounding the DMA’s application and interpretation. You’ll be able to find previous features of the newsletter relating to Apple’s, Google’s, and ByteDance’s workshops here, here, and here.

A slow de-designation

In September 2023, the EC designated Meta for six different services: i) its online social networking services, Facebook and Instagram; ii) its number-independent interpersonal communications services (NIICS), Messenger and WhatsApp; iii) its online intermediation service, Facebook Marketplace; and iv) its online advertising services, Meta Ads. Meta appealed the designation decisions slightly after, and one of the main points of contention of its contesting of the EC’s decision corresponded with the EC’s interpretation of Messenger and Marketplace as separate services to its Facebook service. For instance, on the designation decision, the European Commission highlighted that “it is apparent from the way in which Messenger is provided that, even if that service might have started out as a mere chat functionality of Facebook, over the years it has evolved into a distinct, standalone NIICS beyond Facebook” (para 177 of the designation decision).

On the Facebook Marketplace side, the main point of contention lay within the EC’s interpretation of clause Article 3(1)(b) DMA, which is one of the requirements that an undertaking must comply with to be designated as gatekeeper pursuant to the DMA, namely that it must provide a CPS which is an important gateway for business users to reach end users. The gatekeeper argued that the service only provides for a consumer-to-consumer (C2C) experience since Facebook business users no longer have the ability to create any listing since January 2023, when Meta removed such functionality (para 239). The EC presented a wide array of reasons for designating the service either way as a standalone service, separate from the Facebook social network. First, it set out that the changes performed in January 2023 to the service held no bearing over its designation rationale since it was considering information from 2020-2022 (corresponding to the 3-year view that the designation process applies) (para 256). As a consequence, in that time period, “business users could, legitimately, list their products or services on Marketplace via their Facebook Business page” (para 257). Second, the EC considered that business users could also act in a commercial or professional capacity by listing products and services to end users on the service through their personal Facebook profiles. In fact, the “high frequency on the amount of listing of the same kind may indicate that a user is acting in a professional or commercial capacity” and it is deemed irrelevant that “end users may legitimately generate a high number of listings within a category in the same month for genuine non-commercial reasons since this does not exclude business users from using Marketplace with their personal profile to list goods or services for sale in a commercial or professional capacity” (paras 258 and 259).

In short, the EC did not accept Meta’s allegations that the Facebook Marketplace was a C2C platform and, as such, designated the gatekeeper by estimating one of the thresholds required by Article 3(2) to apply the gatekeeper presumption in a creative manner. To estimate Meta’s yearly active business users, it focused on the best approximation available. Such an approximation consisted of accounting for all Facebook Business Pages with one or more listing on Marketplace as business users and all users, established or located in the Union, which created 28 or more listings in at least one month of the financial year with 80% or more listing being made in the same category (para 277). Bearing in mind that estimation, Meta’s Facebook Marketplace surpassed the necessary threshold for the presumption to be applied. Nonetheless, the European Commission recognised that “it cannot be ruled out that this proxy fails to capture some business users or captures users that are not genuine business users” (para 278).

The end result was that Marketplace was designated as a standalone service. Thus, the gatekeeper was forced to create different versions of its Facebook services to cater to the possibility of a user enjoying Facebook and Marketplace in a bundle and, alternatively, to make access to Marketplace independent so that an end user could enjoy the service without having to be a Facebook user (see pages 20-21 of the 2024 version of its compliance report).

Fast-forward to May 2025, when the European Commission was set to meet the gatekeeper before the General Court to discuss its designation of Facebook Marketplace. A couple of weeks before the hearing, the European Commission announced its decision in April 2025 to Facebook Marketplace’s de-designation since it no longer meets the relevant threshold, giving rise to a presumption that Marketplace was an important gateway for business users to reach end users.

Meta’s legal representatives voiced their concern on the time that the EC took to revise its designation of Marketplace: approximately 14 months since they first filed for the enforcer to reconsider. The gatekeeper requested de-designation by the compliance deadline in March 2024 and heard back from the European Commission only in April 2025, days before the regulator came out with the news that it had decided to drop Marketplace as a CPS. All in all, Meta termed the EC’s passivity as creating an “uneven playing field vis-à-vis the rest of its competitors”, given the massive investments it had to incur within one year, for the service to be removed shortly after.

A half-an-egg omelette

In its first address to the public and the EC, the gatekeeper did not strive to present the flurry of developments they introduced as a consequence of the second iteration of the DMA compliance deadline. Instead, Meta conveyed its ongoing engagement with the EC on its regulatory dialogue discussions and presented its aim to demonstrate a consolidation of its position with respect to its compliance plans with respect to the regulation. In other words, most of Meta’s initial technical implementations set out in 2024 in the first compliance deadline remain unchanged and have been further refined and enhanced to improve user experience and user interfaces, building on the regulatory dialogue with the EC and the feedback it received from stakeholders. The presentations that the gatekeeper’s legal representatives delivered throughout the day followed this general premise.

Notwithstanding, the workshop did not come without some tension when the gatekeeper started to detail how it intends to comply with Article 5(2) DMA in the future, namely via its less personalised ads (LPA) option provided to Facebook and Instagram end users in the EU. Announced and released last November, the LPA option enables end users to further refine the controls for processing personal data on the app directly, which was partially addressed through its 2025 version compliance report on pages 20-21. On that iteration with the EC, Meta displayed a couple of prompts allowing users to select ‘see less’ of particular ad preferences and/or topics.

Against the background of the EC’s fining of the gatekeeper due to its consent or pay ad model, Meta introduced and explained its LPA functionality to respond to the regulator’s qualms.

Prior to detailing the impacts of LPA, however, Meta’s legal representatives performed a brutal beating of the EC’s non-compliance decision, sanctioning its consent or pay model for breaching Article 5(2) DMA by reproducing some of the arguments that it had already raised in that instance. In its own view, the decision ignores the Court of Justice’s ruling in Meta Platforms v. Bundeskartellamt (Case C-251/21), which allowed it to charge a fee and de facto transformed Meta into the only company that cannot avail subscription-based services in the EU (para 129 of the non-compliance decision). Additionally, Meta points to the EC’s doing away with the negative impacts caused by its non-compliance decisions, resulting in the enforcer’s forcing its hand in introducing the LPA functionality.

In its current form, the LPA option enables users to select a less personalised experience (the less personalised alternative required by the non-compliance decision, building on the EDPB’s Opinion 08/2024), resulting in the delivery of direct response ads. In other words, ads designed to elicit an immediate and measurable response from the consumer, typically leading to a specific action like a purchase, sign-up, or visit to a website. In terms of data use, the LPA option entails that the majority of an end user’s personal data is not used for delivering ads, such as data on consumer demographics (e.g., relationship status or education level), organic content (e.g., likes, comments, posts, and photos), third-party interactions on its services and third-party data. According to the gatekeeper, the only personal data used for delivering ads in line with the LPA option relate to the consumer’s age, gender, general location, and context-based data (i.e., the context of the user’s specific choices on a number of the given session when he/she logged into the service). The gatekeeper’s estimates placed the scope of personal data captured by the LPA option at 12% of personal data when compared with the degree of data needed for personalised advertising.

After that, Meta highlighted the three hallmarks that its LPA option brings to the market: i) more user choice in terms of more available controls to users to decide on how the processing of their personal data should be conducted; ii) the drastic reduction in the personal data that the LPA option entails to deliver ads, which is close to 90% less to the personal data processed for delivering personalised ads; and iii) the consequences and trade-offs involved with its introduction, namely the delivering of less relevant ads impacting the user experience and outcomes for advertising relying on Meta’s CPSs to reach consumers. On the latter note, Meta pointed out that when users selected the LPA option, the display of ads resulted in a decrease of 70% of on-site conversions and 60% of off-site conversions, i.e., instances where the consumer clicks on a link to the advertiser’s website.

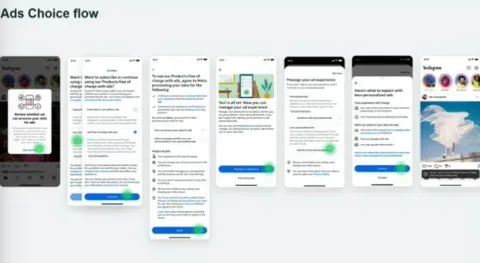

In addition to the LPA option, Meta also fine-tuned the user flow that users must go through to make their choice within the pay or consent subscription model. Those changes were rolled out on June 27 and also incorporated the LPA into the screens shown to the user to get to know about his/her privacy preferences. In a similar vein, Meta also incorporated additional feedback from the European Commission on its previous user flow to further refine the user experience, such as by amending its wording or reducing the number of screens in the flow. The final form of the user flow remains as shown in the screenshot below.

Asked by stakeholders about its recent announcement surrounding WhatsApp’s integration of ads, the gatekeeper refused to provide more details on how the advertising services (and its Meta Ads CPS) would overlap -and potentially combine data- with its messaging CPS.

Meta also demonstrated some progress within particular areas of data-related obligations as a result of its discussions with the European Commission, such as the expansion of the scope of the non-public data to be siloed under Article 6(2) (e.g., the data that is shared and generated by Meta’s advertisers for the purposes of advertising, including through Ads Manager, Meta Business Suite and Meta Business Tools services, page 41 of the 2025 compliance report), or the implementation of regular, automatic and recurring transfers for porting data, granted upon third parties to access end user personal data as enshrined in Article 6(9) DMA (page 50 of the compliance report).

On the note of portability, Meta’s legal representatives also presented a demo of the way in which third parties may become third-party destinations for the porting of an end user’s data. Additionally, they also announced that their currently available portability tools (Download Your Information and Transfer Your Information, see pages 48-50 of Meta’s compliance report) will be merged into a single feature, the Export Your Information functionality, which will be rolled out in the coming weeks. Stakeholders raised questions on the inefficiency of their currently available portability tools for third parties.

Aside from that, Meta was grilled by workshop participants on the ways in which its AI tools, features, and foundation models have been progressively incorporated into its CPSs and how such an integration will permeate the interpretation of the DMA. Meta’s legal representatives responded stoically to those questions by building on the points it had already raised before the Cologne Higher Regional Court relating to the integration of data sourced from Facebook and Instagram to its AI models. According to the gatekeeper, the data inputted into its AI models cannot be categorised as personal data and, as such, will not be captured by some data-related obligations, such as Articles 5(2) and 6(9) DMA. Meta de-identifies, aggregates and tokenises the end user’s personal data coming from its CPSs to its LLMs so that personal data cannot be said to be inputted for this particular purpose. And even if it was, upheld the gatekeeper, its foundation models do not store data in the sense of a dataset, but rather learn through a training exercise. Therefore, it does not perpetually store personal data on a server. Scientific evidence has shown that even if that were to be the case, LLMs face the risk of memorisation, which means that personal data inputted into an AI model (even if it is tokenised and aggregated) may be spewed as a consequence of a user’s prompt.

You can take a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink

The workshop ended with a bang, with Meta’s presentation of the advancements that it has introduced with respect to the implementation of Article 7 DMA, i.e., the horizontal interoperability obligation applicable to messaging services. As opposed to other DMA obligations, Article 7 DMA works with other compliance deadlines in mind and functions with different mechanisms since it is up to the business users to ‘activate’ the rights granted by the mandate. In March 2024 and September 2024, Meta published the reference offers for its WhatsApp and Messenger, setting out the general principles that business users must follow to request horizontal interoperability with the gatekeeper’s messaging services.

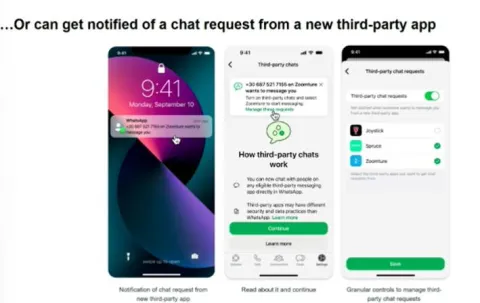

Following their publication, Meta further refined its approach to Article 7 DMA and made some changes to its technical implementation of the provision. At the outset, an end user wishing to interoperate via WhatsApp/Messenger must opt in to such an option (pages 60-64 of the compliance report). Upon that choice, once third-party business users integrate and roll out their interoperability solution with WhatsApp/Messenger receive a notification that such a feature is available to them (page 61 of the compliance report).

Following stakeholder and EC feedback, Meta provides additional ways for users to access the interoperability options available to them, such as receiving a reachability ping sent directly by the third party (even if the user has not installed that app on his/her device) via SMS, in those instances when the consumer has explicitly opted into such a functionality, as seen below.

Despite the gatekeeper’s willingness (and efforts) to make the provision work for third-party messaging services seeking access, Meta reported that no third party has rolled out its interoperability solution with either WhatsApp or Messenger. The gatekeeper, however, anticipates that a new interoperability solution will be rolled out soon on WhatsApp based on its discussions with third parties, since it has seen no traction in the provision of its Messenger service. In its own view, such a solution corresponds with the uncertain consumer demand that access seekers face in light of the high level of investment required to make their interoperability solutions economically viable.

In the round of questions, one got the sense of a better set of reasons why that might be. Most stakeholders (and access seekers) pointed out the hurdles they were facing in terms of rolling out their interoperability solutions, which precisely came from the requirements that the gatekeeper had imposed on them when negotiating the terms of access, based on the general principles set out by the reference offer. For instance, some access seekers highlighted Meta’s narrow reading of the notion of ‘individual users’, the limitation of the interoperability solution to only one device (i.e., the smartphone), and the inherent restriction of its deployment to the EU. On the latter aspect, several stakeholders catering to messaging services revolving around the provision of privacy and secure apps to their consumers stressed that they could not disclose to Meta the localisation of its users since they did not have any visibility on that data themselves. Meta’s legal representatives kept close to the letter of the law and stressed that it could do nothing about these types of situations since the DMA compels it not to go beyond the EU’s territorial boundaries.

As Meta’s legal representatives pointed out throughout the workshop, the same expectations cannot apply to a cook when she is making an omelette with three eggs as opposed to when she is making the same omelette with half an egg. The DMA entails a sacrifice in terms of business and market outcomes whilst redistributing rents in favour of business users from the gatekeeper’s ecosystems. Rent redistribution does not, however, apply transversally and without friction as the EC wishes.

___

This is a re-post of the original piece published on The DMA Agora.

You may also like