Alphabet’s Second DMA Compliance Workshop: A Self-Reported Engaged Gatekeeper

July 18, 2025

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) became entirely applicable on 7 March 2024 for most gatekeepers. By then, the gatekeepers issued their compliance reports documenting their technical solutions and implementation of the DMA’s provisions under Article 11 DMA, as well as their reports on consumer profiling techniques as required under Article 15 DMA. A year later, six gatekeepers submitted an update to the first version of their compliance reports (they can be found here).

I will be covering this year’s compliance workshops held by the European Commission, where the gatekeeper representatives meet stakeholders to discuss their compliance solutions to the DMA’s obligations (and the updates they introduced since 2024). You’ll be able to find a previous feature of the newsletter relating to Apple’s workshop here, and we’ll consider Alphabet’s (aka Google’s) compliance workshop in the present piece.

A gatekeeper's regulatory cold seat

At every single compliance workshop, EC officials reiterate that they intend to enforce the DMA both subject to the letter of the law and also to its spirit. From Google’s attitude throughout the compliance workshop, there seems to be some misalignment with the EC’s intentions in making business users thrive on the business opportunities granted by the DMA as a piece of regulation. Some questions formulated by workshop participants were brushed off by Google’s legal representatives in a couple of words, whilst, at times, the only valid excuse for not engaging with the stakeholder proposals and suggestions lay within the strict reading of the letter of the law. I am not saying that Google was wrong to take such an attitude, but it might have to do just what Ross Geller shouted on a staircase when he was moving apartments: PIVOT!

Despite the cold shoulder that Google gave to most workshop participants, its legal representatives self-reported as the number one gatekeeper in terms of engagement with both the EC and stakeholders. In this sense, Google’s first remarks were devoted to pinpoint the main issues of contention with the DMA’s enforcement since its obligations started to apply in March 2024, such as the importance of not conflating DMA compliance with real-life (and beneficial) outcomes brought to the business users depending on its core platform services (CPSs) or the fact that such an intense compliance strategy is not economically sustainable for Google whilst it intends to innovate in delivering useful products for business and end users. On this same note, Google put forward the CCIA-commissioned Economic Impact of the Digital Markets Act on European Businesses and the European Economy report to highlight the economic fatalities that have taken place as a consequence of the DMA. For instance, the economic evidence shows that, at the level of the EU economy, the average revenue loss of those businesses using online platform services to sell to end users lies between EUR 8.5 billion and 114 billion.

The sessions running in the morning of the compliance workshops started with a colourful mix of provisions that the EC had set on its agenda, notably Articles 6(3), 6(4), 6(7), and 6(12), touching upon Google’s compliance solutions relating to its Android OS and how it caters to alternative app distribution channels as well as to choice screens to facilitate switching on browsers and search engines.

Before the gatekeeper’s intervention, the EC highlighted the few priorities it had set out when engaging with Google on its regulatory dialogue when implementing these two provisions, such as the choice screen’s design, the placement of browsers installed as defaults (i.e., the hotseat position), the process of uninstalling Google apps on Android devices as well as the end user journey to install third-party apps (via sideloading) and alternative app stores.

Stemming from the EC’s cue, Google presented the changes it introduced in June 2024 and the end of the year relating to how it rolls out its choice screens showing alternative vendors of browsers and engines (as already set out in its 2025 compliance report, pages 126-130). For instance, Google transformed the choice screen’s functionality to make it part of a blocking experience whereby end users were forced to make a choice in order to be allowed to continue using Chrome, to increase user engagement with the prompt. As a result, Google was able to confirm that, at the end of May 2025, choice screens had been shown on 472 million devices in desktop and mobile format.

Workshop participants raised concerns surrounding the prompting of Google Search in other environments where Google Search was not set as a default, for instance, when an extension is displayed on Google Chrome. Google echoed those concerns in reverse, by saying that it could not control those instances where the prompt was rolled out and, in fact, read out comments from users reflecting their frustration with the user flow as currently shown. Additionally, competing search engines to Google Search representatives also pointed out that the choice screen is not triggered in some contexts where OEMs are contractually bound with Google to pre-install and set Google Search as a default, e.g., on the Samsung Internet Browser. Google’s legal representatives claimed they had no bearing over it, since Article 6(3) compels it to display the choice screen in the context of the gatekeeper’s browser, and not in any other format.

Furthermore, a few stakeholders pushed Google’s buttons to make the choice screen’s impacts readily available to the users, i.e., via the placement of the new default browser in the hotseat. The hotseat refers to the lower deck displayed at all times on a mobile device. Apple’s implementation of Article 6(3) DMA entailed that once an alternative browser was set as the default on iOS, it would be installed on the hotseat, replacing Safari’s placement. Stakeholders asked for equivalent measures to be adopted by Google. Once again, however, Google’s legal representatives stressed that Article 6(3) did not require such an action and, therefore, would not be moving forward with those changes any time soon.

Aside from the choice screen, Article 6(3) DMA is much broader in its scope, since it also establishes that the gatekeeper must enable switching of default apps. Before the challenge, Google presented three particular ways in which users can easily switch their default apps on Android: i) through the devices settings menu; ii) through disambiguation boxes, i.e., choice options shown at a point in time when the user performs a given action, such as the opening of a pdf file; and iii) in-app prompts that third-party developers can show when they are downloaded on Android (page 108 of its compliance report).

Additionally, the provision also requires gatekeepers to fine-tune their default settings so that they enable the easy uninstallation of any app on their OS. Greater controversy arose on this particular point. Google, on one side, defended that all apps on Android can be uninstalled, despite the fact that its own compliance report highlights that “certain apps on Pixel devices that are essential to the functioning of the operating system or of the device cannot be uninstalled” (page 108 of its compliance report). Workshop participants ran to point out the discrepancy and added to the statement the fact that Google does not really enable users to uninstall its own apps, since a full deletion of code is not performed as a consequence. Similarly, assertive participants pointed out that Android did not even point out the difference clearly to users since the option reads ‘deactivate’ and not ‘uninstall’. To those calls, Google used the CMA’s Mobile Ecosystems Study and Mobile Browser Market Investigation as shields to the allegations, where the UK competition authority had highlighted that remaining inactive remnant code could be equivalent to uninstallation, since it produced the same effects as full deletion, i.e., it was hidden from users, did not take significant memory and could not be reactivated.

Furthermore, Google was quite adamant in defending that it runs an open ecosystem where developers have broad freedom to distribute their apps on Android through three particular means, abiding by the terms of Article 6(4) DMA. First, the pre-installation of apps, given that developers can strike deals with OEMs or carriers for their apps and app stores to be preinstalled, such as Epic’s recent agreement with Telefónica to pre-install its Epic Games Store on all new compatible Android devices. According to the gatekeeper, OEMs have pre-installed a non-Chrome browser on 70% of European Android devices. Second, the developer’s distribution of their apps through a wide range of other third-party app stores, which most developers have chosen to do. In line with the data put forward by Google, 46% of developers distribute through multiple Android app stores, and two-thirds of Android devices have a non-Play app store preinstalled on the device. Finally, sideloading, aka users downloading apps and app stores directly from the internet or via other sources such as messaging or app transfer apps. Based on Google’s data, more than 50% of Android users have sideloaded apps at least once on their devices.

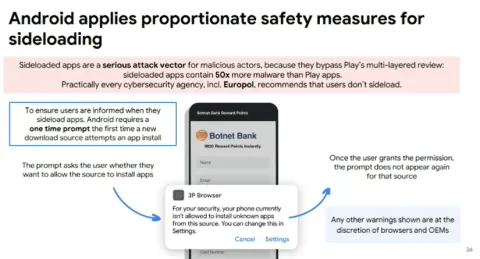

The discussion with stakeholders on sideloading was the thorniest of them all since Google defended that sideloading risks outweigh a developer’s right to offer a seamless and frictionless downloading experience to the user. To that effect, Google has introduced a one-time prompt when a new download source attempts to install an app to warn the user about the risks of sideloading, as shown in the image below. If the user is not scared off by the warning, then Google redirects the user to the Settings page, where such a sideloading blocking for that particular developer can be overridden directly by the user. Once the user modifies the settings feature, the user will be able to download the app directly onto its device.Stakeholders in the room raised their concern on the scare screen shown by Google to users wishing to sideload on different fronts by denouncing that the prompt caused a 60% drop in their downloads (for some of them). Google committed to getting back to them on its new plans relating to the user flow design, since it will re-design and release it in the coming months to reduce the three steps to one or two, at most. The update will be improved and rolled out at the end of the year. In addition, a couple of workshop participants wondered whether Google could make its best efforts to create a new functionality enabling it to whitelist those apps that it had already reviewed on Google Play when they were sideloaded via a website. Google’s legal representatives confirmed that the proposal was not technically feasible. Taking the argument to its extreme, the gatekeeper could not assume the review of those apps on a case-by-case basis, since that would triplicate its costs for conducting app reviews, which currently account for half a billion euros annually.

A bit of time was also allocated to discussing how Google complies with the FRAND terms it must provide when granting access to its search engine as set out under Article 6(12) and the vertical interoperability obligation set in Article 6(7) DMA. Concerning the latter, no particularly poignant issues were raised that weren’t included in the previous compliance workshop held by the EC with respect to Google.

Notwithstanding, Google’s implementation of Article 6(12) DMA in the space of its Google Search CPS was somewhat more cryptic (as it has been on its compliance reports, see page 192 of its 2025 version and page 198 of its 2024 version). In previous iterations, Google already disclosed that it runs a “free and open (service) for business users (websites)” and “does not require websites to enter into any contract terms that govern the provision of services by Google Search to the websites that are in Google’s index”. Additionally, it already published EEA general conditions of access providing that “as long as a website is published on the web and meets the minimum technical requirements (ie, the page works and has indexable content, and Googlebot is not blocked), it is eligible to be indexed by Google Search”. In that sense, the gatekeeper applies its conditions of access “equally and non-discriminately to all business users with websites in the EEA”.

Google provided a few clarifications on its previous statement and referenced the large amount of information available to business users on the indexing of its search results through its Google Search Essentials website, where they can access instructions to increase their chances of being discovered via the search engine. Stakeholders were uninterested in the provision’s application as much as the gatekeeper demonstrated to be.

AI thing of beauty is a joy forever

The second session of the workshop strived to clarify Google’s integration of AI into its CPSs and how those integrations impacted its current compliance plans surrounding the DMA. The short version is not much. Google did not provide a shorter version, but rather a longer one where it provided a full account of its history surrounding AI and how it had integrated AI functionality prior to the gen-AI boom, for instance, BERT conducting query analysis and retrieval works on its search engine since 2019 or Gmail nudging end users to look out for un-answered emails.

Surprisingly, it missed out on detailing how its technical implementation of the DMA would look as stemming from its AI Overviews (already available in the EU at the top of every single user’s search responses) and AI Mode (rolled out in the US, and not yet in the EU) integrations. The only insight that Google provided related to its general interpretation of the interaction between AI as a technology and the DMA. All AI functionalities are not to be considered as standalone or separate services from its 8 CPSs, but rather as part of them.

The (deliberate) irony was not lost on many workshop participants drilled down on both functionalities and enquired about the compliance of the prohibition on cross-using and combining personal data across CPSs, i.e., Article 5(2) DMA. Google did away with the concerns quite quickly by simply stating that the consent safeguards that it had previously introduced generally for its CPSs would apply to all AI functionalities (see pages 9 of the 2025 version and pages 10-14 of the 2024 version of the compliance report). Moving forward on concerns surrounding Google’s potential discriminatory implementation of AI Overviews for ads and shopping results, as well as for news content, Google’s legal representatives stressed their intention for the DMA “to regulate, and not to suffocate”. As such, AI Overviews represents the evolution of its Google Search service, and several rounds of experimentation and iteration with regulators will have to be performed to fine-tune the potential concerns arising from its practical deployment.

Representatives of editorial media publishers also raised questions about the interplay of AI Overviews with the sudden dip in referrals coming from Google Search to their websites sustaining journalism. According to their data, those referrals decreased by 50-60% since AI Overviews was launched, reducing their business opportunities as a consequence of their reliance on ad revenues. Studies and commentators have termed the phenomenon as the ‘great decoupling’ of Google Search since the growth of impressions in AI-powered SERPs no longer translates into a proportional growth in clicks. Google strenuously denied such allegations and referenced different sources of data pointing to a more nuanced picture in terms of referral traffic and the direction of traffic flows stemming from the introduction of AI Overviews. According to the gatekeeper, AI Overviews supports a greater diversity of publishers appearing in search and reinforces the quality of traffic (since users stay longer on a publisher’s website).

Following the indications of US court documents released on Google’s online search trial, these same workshop participants wondered whether Google had provided any opt-out option so that their journalistic content would not be included in AI Overviews if they chose to exercise such an option. According to Google’s legal representatives, such a mechanism is already available for AI Overviews through the NoSnippet Meta Tag.

Data-related features and an ineffective provision of ranking, query, click and view data

On the second-to-last session, Google focused on its data-related obligations, notably Articles 5(2), 6(9), and 6(10), but did not provide any additional information from what we have heard from it as stemming from the compliance reports.

To provide a small recollection of facts, Google implemented back in 2024 two technical solutions to comply with Article 5(2), namely a consent moment shown to users when they access Google Chrome to consent to the linking of data across its CPSs and the establishment of new infrastructure data controls to regulate the flow of data from and to relevant services consistent with user consents (pages 10-14 of the 2024 version of the compliance report). According to Google, up to 438 million users had been shown the consent screens and 97,7% of them (428 million) had made a decision. Asked by participants to provide further information on consent rates, the gatekeeper refused to disclose them.

The only change that the consent moment may experience will precisely come as a result of regulatory intervention by the Italian competition authority. In a case triggered in July 2024, the AGCM took issue with Google’s rolling out of its consent screens because they potentially could condition the freedom of choice of the average consumer and would induce them to make commercial decisions that they would not have taken otherwise. In short, Google’s Article 5(2) implementation could constitute a misleading and aggressive commercial practice in the terms presented by the Italian consumer protection regime.

In a similar vein, Google set out its approach towards compliance with Articles 6(9) and 6(10), which have not been updated since the gatekeeper last released its 2025 compliance report (see pages 20-30 and 37-73 of the 2025 compliance report). Stakeholders raised questions on the rationale underlying Google’s exclusion of certain Android data from its portability solutions, to which the gatekeeper responded by arguing that such data could not be classified as personal data under Article 6(9) DMA. At the end of the workshop, Google presented a live demonstration of how its Data Portability API works on both the end and business user side, as shown in the image below.Moreover, Google also presented its compliance approach towards compliance with the obligation under Article 6(11) forcing it to provide third-party undertakings providing online search engines, at their request, with access to FRAND terms to ranking, query, click, and view data in relation to free and paid search generated by end users on its online search engine. The particular provision does not star so prominently in the headlines, but it is a key obligation to ensure contestability in the search space. To facilitate the provision of data, Google designed its Search Data Licensing Program, compiling a dataset of over one billion distinct queries across all 30 EEA countries so that rival search engines can license it for the purpose of improving search functionality. The database contains 1-5 TiB of anonymised search data per quarter, with around 30 billion rows covering query strings, extensive information on the Google results shown and their ranking, and what users clicked on. The database is available on a quarterly basis for up to three years at FRAND pricing, providing flexibility to business users if they only wish to take and pay for subsets of the dataset (pages 193-194 of the compliance report and Google’s presentation at last year’s compliance workshop).

Moreover, Google also presented its compliance approach towards compliance with the obligation under Article 6(11) forcing it to provide third-party undertakings providing online search engines, at their request, with access to FRAND terms to ranking, query, click, and view data in relation to free and paid search generated by end users on its online search engine. The particular provision does not star so prominently in the headlines, but it is a key obligation to ensure contestability in the search space. To facilitate the provision of data, Google designed its Search Data Licensing Program, compiling a dataset of over one billion distinct queries across all 30 EEA countries so that rival search engines can license it for the purpose of improving search functionality. The database contains 1-5 TiB of anonymised search data per quarter, with around 30 billion rows covering query strings, extensive information on the Google results shown and their ranking, and what users clicked on. The database is available on a quarterly basis for up to three years at FRAND pricing, providing flexibility to business users if they only wish to take and pay for subsets of the dataset (pages 193-194 of the compliance report and Google’s presentation at last year’s compliance workshop).

The gatekeeper fleshed out a bit more the general statements it included in its 2025 version of the compliance report relating to the additional tweaks it had introduced to the technical implementation of the solution (page 187 of the compliance report). First, it confirmed it had “introduced a new pricing tier”. The gatekeeper’s legal representatives confirmed that it would apply a new 50% cheaper pricing tier for online search engines with EEA search revenues below EUR 0.05 billion and flexible pricing across different countries and sample sizes. Second, the report highlighted it introduced “further optionality for potential recipients on the scope of the license”. At the workshop, Google confirmed that it would provide a one-time fractional sample for competing online search engines to receive a one-time 5% fractional dataset before they decide whether they wish to purchase the full dataset or fractional 10% or 50% options. Finally, the report noted that the gatekeeper “made technical changes to increase the volume of the dataset in a privacy-safe manner”. Those changes include an update to query recovery techniques, which is a new technical solution to disclose more data in a privacy-safe manner.

The crux of the provision, however, lies in how Google applies anonymisation to the click, query, ranking, and view data available to competing search engine providers. To that end, Google anonymises the data based on frequency thresholding, including all queries entered by at least 30 signed-in users globally over the 13 months before the end of the relevant quarter and excluding data on results viewed by fewer than 5 signed-in users in a given country and per device type. In practice, as disclosed by representatives from competing search engine providers, Google’s Article 6(11) data does not strike the right balance between utility and anonymisation, since most distinct queries are removed from the dataset. In other words, according to their estimates, only 1-2% of the whole database is actually productive data that they can use to compete on the merits with the gatekeeper. Before these allegations, Google argued that no currently available anonymisation techniques allow it to provide a robustly anonymised dataset that simultaneously fulfils the obligation’s objective.

Google calls let’s stick to the letter of the law, whilst shielding compliance under the cover of exceptions lying in the DMA’s foundations.

______

This is a re-post of the original piece published on The DMA Agora

You may also like