A Steel Fist Inside A Velvet Glove

March 1, 2014

One of those tips was about keeping it real and suggesting a 'steel fist inside a velvet glove' posture when protecting important interests (aka things that are fundamentally important to you) at the mediation table.

Judging from the feedback at and after the competition that phrase struck a chord – like law student and soon to be lawyer, Lamice Nasr of the Saint Joseph University in Beirut, Lebanon who wrote saying the “steel hand in a velvet glove theory is now a fundamental aspect of my professional career".

But what does it mean?

Well, for me its as much about how (often the velvet) you say something as what (often the steel) you say at mediation. Like many aspects of mediation, you can say almost anything so long as how you say it is appropriate.

So for instance, you might give early signposts of no-go zones instead of hitting them with a bump down the track and risking surprise and resulting impasse.

Something like this in your opening might work... "you probably need to know that while we can talk about X or Y, and we want to do that sooner rather than later, when we get to A and B, we will find it the hard to depart from where we've already signalled we are - but we do want you to know the reason for that - because we need you to see us as constructive albeit firm in some important areas - as you will be no doubt around your C and D…."

To explain how it is when what is important to you seems different from what is important to them, I turn to my friend Margaret Halsmith of Perth, Australia. Here she explains what happens when a neutral facilitates an even handed approach to exploring and explaining what is important to each of the parties at mediation.

Here’s a series of diagrams I developed to describe how you know when you’re in a mediation and when you’re not, and how you know when you’re mediating and when you’re not.I developed these diagrams to explain mediation to my clients and to tertiary students. I’m often asked for them, so here they are.

Mediation is not …

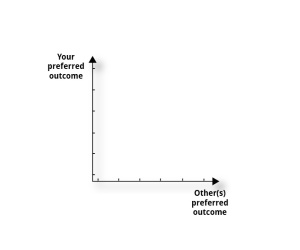

Mediation is not compromising on your preferred outcome.

When your preferred outcome is to go in another direction from another person’s preferred outcome there is often conflict. How acceptable is the other person’s preferred outcome to you?

Their preferred outcome may be low in acceptability to you. Your preferred outcome may be low in acceptability to the other person. You may each be saying ‘My way or the highway.’

If a settlement is what you need, you may have to give in and the other person may have to give in. Settlement comes from each of you accepting an outcome less than your preferred outcome.

An efficient, competitive settlement will be along the limit of settlement which means that both you and the other will have given in to some extent. An inefficient settlement will be in the area of potential settlement which means that you and the other person will have given in more than you needed to.

This is a settlement conference which is sometimes mistaken for mediation.

There is another way.

Mediation is …

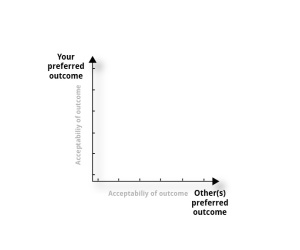

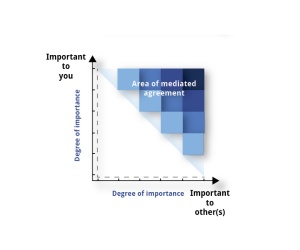

Mediation is reaching a creative agreement on what is important to each of you

When what is important to you seems different from what is important to the other person there is often disagreement. When a neutral person facilitates an even handed approach to exploring and explaining what is important to each of you, you are on the way to mediation.

A creative, cooperative agreement will be reached in the area of mediated agreement which means that you and the other person have designed an agreement that adds value to the competitive agreement above. The sky is the limit.

An efficient, cooperative agreement will be along the line of likely settlement, which means that both you and the other person have reached an agreement which meets maximum criteria for what is important to each of you. Compare the outcome of mediation in this diagram with settlement conference above.

The difference between these approaches is in the questions that are asked throughout. In a settlement conference, the persistent questions will be ‘What is your preferred outcome?’ and ‘How much will you compromise?’. The primary question of a mediation will be ‘What is important to you?’

You have a choice between competition and cooperation and the results that flow from each.

For more clear thinking articles from Margaret please visit her at http://margarethalsmith.wordpress.com/

You may also like

Diego Faleck

Dear Geoff, I do agree without question that it is an extremely good advice to “give early signposts of no-go zones instead of hitting them with a bump down the track and risking surprise and resulting impasse”. Considering you have prepared carefully for your negotiation, meaning that you know your interests well and analyzed what is important to convey to the other party, and you are up to date with your assertiveness skills, one can say that explaining your no go zones to the other side is essential. But, talking about realism, it is also the easy part. The trick is, how do you make it credible? How do you get the other side to believe in it and roll with it in the negotiation? In fact, you can say almost anything at the table as long as how you say it is appropriate, but saying things that has an effective impact in the other party, and allow you to effectively get what you want and advance your interests, perhaps require more thoughtful measures. I think you have signaled those in your example, when you demonstrated briefly the need for an explanation. I would like to dwell a little bit deeper on this. And I think it is important because this is a critical issue that is not actually reflected in score-sheet of the mediation Competition you mentioned, used to evaluate student’s performances. I have to admit I am not a fan of the fist metaphor. The idea of a fist with a velvet glove brings about some type of thrust, with nice words. Since nobody wants to loose in the market and reciprocity is a golden rule in negotiation and mediation, I would say, if it looks like a fist, you may get another fist back, also with a velvet glove. And you may simply reach an extremely polite stalemate. Negotiators often deploy tactics to influence the other side’s perceptions. Every negotiation begins with high expectations from each side. The majority of negotiations begins with resistance, and one should not be intimidated by hearing some type of “no” or “fist” in the beginning of the session. That is only natural. In fact, most cases begin with positions and expectations far apart. It is the role of every negotiator to probe for the other side’s limits or reservation value, and protect her own. Many would argue that one should try to get as much as she can, as long as the other side is left minimally satisfied. Merely stating your no go won’t solve the problem. You need to make it in a credible way. There are ways to do it. In my view, the first asset that may help you in this task is your reputation. This is why maybe a good advice for students in this regard, is to care about developing a reputation for being straight shooters. If you have a good reputation, as an honest, transparent and fair negotiator, you certainly have an edge in making the other side understand your no deal. If your reputation hasn’t reached the table you are at, another advice, be impeccable. That is two-fold. First it means prepare your framework to present the idea of your no go carefully. There has to be a logical reason behind it, one that is easy to explain. You need a logical reason, one that stands, to support why you have no way other than playing the chicken game to the end. You have to avoid inconsistencies in your speech, strategy and behavior and pay attention to your non-verbal cues. You may also make use of anchoring and meta-anchoring skills. It is also important to be ready to discuss the issue open-heartedly, to answer all the questions you will get and demonstrate your strong willingness to continue thinking about options. If the other party realizes you are also concerned about their interests in finding a solution, by the use of the rule of reciprocity, you may get to advance your own interests. You should also make sure that this is a true interest you are protecting, not a position. I’ve mediated many cases starting with strong flagging of no-go zones, and in the end, after expectations were naturally worn out in the process, parties made concessions on those issues, and left the table truly satisfied with the outcome. William Ury presents a superb framework to deal with this type of situation, in his work “The Power of a Positive No”. He suggests you should “sandwich” your no. Start with an “yes” to yourself, meaning, explaining the reasons why you have a no go zone. Then, present what your no go zone is. And then, present the second “yes”, the second slice of the bread, bringing about a positive discussion about the future and the development of options. Healthy negotiators don’t give in to strong tactics in a negotiation table. Simply asserting your “no deal” will not solve the problem. You have to do it carefully. People give in to logic, to the understanding that your warning is credible, that you will not give in, and that what you expect them to do in return is feasible for them and take into account their interests. The problem is not solved on a single statement, but a bigger problem could be created by it. I understand your point about making clear what your interest is – what you called a steel fist, and doing it carefully – what you mean by using a velvet glove. I agree with you completely in substance. My only concern is that this metaphor is easy to be misunderstood and misapplied. A fist, a symbol of aggressiveness, polite or not, could compromise the entire negotiation, and prevent it from reaching the integrative levels presented later in your piece. I would rather get a sandwich than fist with a velvet glove. Who wouldn’t? Cheers from Brazil, Diego Faleck