UN Tax Committee Confronts New Challenges from AI to Health Taxes

October 31, 2025

By Pramod Kumar Siva and William Byrnes of Texas A&M Law

1. Previous Comments, Recommendations, and Policy Analysis to the OECD and UN

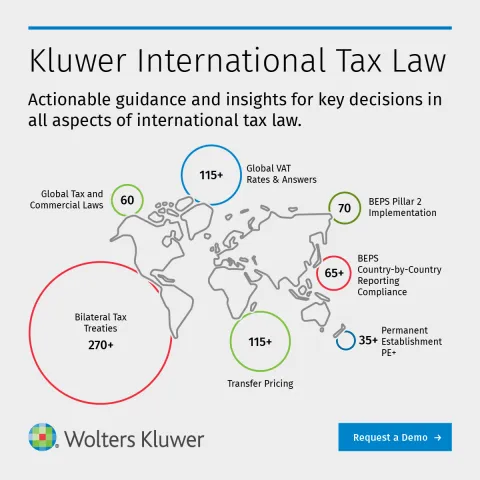

Pramod Kumar Siva and I have been closely following and engaging via comments and attendance, with the post-BEPS international tax initiatives of the OECD, the United Nations, and U.S. responses (as have our most esteemed Texas A&M faculty colleagues Dr. Lorraine Eden, Dr. Andrew Morriss, and Dr. Charlotte Ku). Since 2019, we have submitted a variety of comments and recommendations in respect of the OECD’s post-BEPS output of Pillar One and Pillar Two that are published here within the Kluwer International Tax Blog, two examples being: Comments and Recommendations for the OECD “Unified Approach” to Digital Taxation; and Recommendations for the Pillar One and Pillar Two Blueprints. Readers may further be interested in our recent Pillar Two policy recommendation: Good Intentions, Bad Tools: A Case for Repealing the UTPR.[1] Also available on the Kluwer International Tax Blog, we submitted comments and recommendations to the United Nations Intergovernmental Committee[2] as it drafted the International Tax Cooperation Convention: Comments with Proposed Text for the UN Intergovernmental Committee Drafting the International Tax Cooperation Convention.

With this article, we provide our readers an overview of the United Nations’ International Tax Committee of Experts[3] most important past initiatives and those discussed and voted upon October 21 through 24, 2025, to be addressed within work streams during the four-year term that began July 30, 2025 with the announcement of the newly appointed country-delegates (who speak in their personal capacity rather than on behalf of their government positions).

[1] Siva, Pramod Kumar and Byrnes, William, Good Intentions, Bad Tools: A Case for Repealing the UTPR (July 21, 2025). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5378629 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5378629

[2] Intergovernmental Negotiations for UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. Available at https://financing.desa.un.org/unfcitc.

[3] 31st Session of the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. Available at https://financing.desa.un.org/events/31st-session-committee-experts-international-cooperation-tax-matters.

2. Background of the United Nations International Tax Key Initiatives

2.1 UN Transfer Pricing Manual 2013

On May 29, 2013, the United Nations launched its “Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries” (UN Transfer Pricing Manual).[1] This manual evolved from the earlier October releases of 2012 and working draft releases of 2011 and 2010. The manual was developed to respond to the need “for clearer guidance on the policy and administrative aspects of applying transfer pricing analysis to some of the transactions of multinational enterprises (MNEs) in particular.” The UN Transfer Pricing Manual states that it is designed for application of the globally accepted “arm’s length standard.” In a communique released August 9, 2013, the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters stated that the Committee’s considerations upon intangibles had not yet ripened for inclusion in the 2013 version, but that the Committee was preparing a detailed guidance on intangibles in a separate chapter of the manual for the next update.[2]

At the 2014 tenth session and in preliminary meetings, the Committee discussed new commentary for the UN Model Double Tax Agreement Article 9, including:[3]

1. recognizing the arm’s length principle as found in the United Nations and OECD Model Conventions;

2. continuing to remind countries that the application of the arm’s length principle presupposed transfer pricing rules in domestic legislation;

3. replacing the statement by the former Group of Experts, the predecessor of the Committee, with quotation from the OECD commentary on article 9;

4. quoting OECD language on how that organization categorized the international significance of the OECD Guidelines; and

5. reflecting a view agreed by Committee members on the relevance of the OECD Guidelines and the Transfer Pricing Manual in helping to implement the arm’s length principle.

[1] See http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/documents/UN_Manual_TransferPricing.pdf.

[2] United Nations Economic and Social Council, Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, E/C.18/2013/4 (Aug 9, 2013), available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=E/C.18/2013/4&Lang=E.

[3] Report on the tenth session of the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, United Nations (October 27, 2014). Available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=E/2014/45&Lang=E.

2.2 UN BEPS Handbook 2015

The eleventh session of the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters was held from October 19 to 23, 2015, and addressed revisions to the UN Transfer Pricing Manual in consideration of the OECD’s BEPS initiatives. Following up on the previous communique, the UN Transfer Pricing Manual proposals for amendments include an additional chapter on the treatment of transactions relating to intangibles, a further chapter on intra-group services and management charges, additional text on business restructuring, and an annex on available technical assistance and capacity-building resources. The UN Committee of Experts published the United Nations Handbook on Selected Issues in Protecting the Tax Base of Developing Countries (UN BEPS Handbook 2015).[1] The Financing for Development Office (FfDO) undertook the project to supplement the OECD’s BEPS project from the perspective of developing countries. This project focused on several issues of particular interest to developing countries, including, but not limited to, matters covered by the OECD.[2]

• Neutralizing the effects of hybrid mismatch arrangements;

• Limiting the deduction of interest and other financing expenses;

• Preventing the avoidance of permanent establishment status;

• Protecting the tax base in the digital economy;

• Transparency and disclosure;

• Preventing tax treaty abuse;

• Preserving the taxation of capital gains by source countries;

• Taxation of services;

• Tax incentives.

An updated and expanded second edition of the UN BEPS Handbook was published in 2017.[3] This second edition updates the chapters from the 2015 edition to reflect the final outputs of the OECD project on BEPS, as well as the latest developments in the work of the United Nations Committee of Experts on tax base protection for developing countries. The second edition includes two new chapters that address base-eroding payments of rent and royalties and general anti-avoidance rules (GAARs).

The proposal for the chapter on intra-group services considered that tax authorities of countries of service recipients sought to ensure that only genuine service charges are allocated to service recipients, while the authorities of countries of service providers are concerned with service charges being allocated to group members with an appropriate mark up. Multinational enterprises sought to ensure that service costs are allocated to group members and have appropriate profit margins. Developing countries are concerned about base erosion through service charges, such as claiming that such high-margin services as strategic management and research and development had been rendered when it is hard to identify benefits. The proposal distinguished between high-margin and low-margin services. “Safe harbors” for non-essential services and a de minimis rule, with a focus on simplicity and resource savings, were also under discussion, as well as Cost Contribution Arrangements.

[1] Available at http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/handbook-tb.pdf.

[2] UN BEPS Handbook 2015 at p 8. See documents of the Subcommittee on BEPS for Developing Countries, available at http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/tax-committee/tc-beps.html.

[3] See https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/publications/handbook-tax-base-second-edition.html.

2.3 UN Transfer Pricing Manual 2017

These discussions led to the revisions of the 2017 United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries, undertaken by a Subcommittee of the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters. The revisions were developed from the following perspectives that:[1]

• it reflects the operation of Article 9 of the United Nations Model Convention, and the Arm’s Length Principle embodied in it, and is consistent with relevant Commentaries of the U.N. Model;

• it reflects the realities for developing countries, at their relevant stages of capacity development;

• special attention should be paid to the experience of developing countries; and

• it draws upon the work being done in other fora.

The 2017 UN Manual revisions include:

• A revised format and a rearrangement of some parts of the Manual for clarity and ease of understanding, including a reorganization into four parts as follows:

o Part A relates to transfer pricing in a global environment;

o Part B contains guidance on design principles and policy considerations; this Part covers the substantive guidance on the arm’s length principle, with Chapter B.1. providing an overview, while Chapters B.2. to B.7. provide detailed discussion on the key topics. Chapter B.8. then demonstrates how some countries have established a legal framework to apply these principles;

o Part C addresses practical implementation of a transfer pricing regime in developing countries; and

o Part D contains country practices, similarly to Chapter 10 of the previous edition of the Manual. A new statement of Mexican country practices is included and other statements are updated.

• A new chapter on intra-group services.

• A new chapter on cost contribution arrangements.

• A new chapter on the treatment of intangibles.

• Significant updating of other chapters.

• An index to make the contents more easily accessible.

[1] United Nations Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters’ Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries (Apr 4, 2017) (hereafter “2017 UN Manual”). Available at http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Manual-TP-2017.pdf.

2.4 UN Transfer Pricing Manual 2021

On April 27, 2021 the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters published the third edition of the United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries.[1] In its third edition, the 2021 UN Manual revises existing text and adds new chapters and sections, including more country practice chapters. Note that the transfer pricing issues specific to the extractive industries is addressed in a transfer pricing chapter within the United Nations Handbook on Selected Issues for Taxation of the Extractive Industries by Developing Countries.[2]

The 2021 UN Manual contains new and revised content for financial transactions,[3] profit splits,[4] centralized procurement functions,[5] on group synergies,[6] on customs valuation,[7] and comparability issues.[8] The third edition also includes new content on establishing transfer pricing capabilities within tax administrations.[9]

The UN Manual addresses the practical implementation of a transfer pricing regime in developing countries and shares examples of country practices from developing countries, such as Brazil, China, India, Kenya, Mexico, and South Africa.[10]

The 2021 UN Manual adopted a four-digit paragraph numbering system, and the inclusion of additional paragraphs necessitated a citation change for most content from the second edition of 2017 to the third edition. This treatise is updated to reflect the most current 2021 UN Manual.

[1] United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries, Third Edition (April 27, 2021), hereafter referred to as the “2021 UN Manual”. Available at https://www.un.org/development/desa/financing/document/united-nations-practical-manual-transfer-pricing-developing-countries-2021.

[2] United Nations Handbook on Selected Issues for Taxation of the Extractive Industries by Developing Countries (2018) available at https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3801187?ln=en.

[3] 2021 UN Practice Manual ¶ B.9.

[4] 2021 UN Practice Manual ¶ B.4.6.5.10.

[5] 2021 UN Practice Manual ¶ B.5.7.

[6] 2021 UN Practice Manual ¶ B.6.2.5.13.

[7] 2021 UN Practice Manual ¶ B.4.2.7.

[8] 2021 UN Practice Manual ¶ B.3.

[9] 2021 UN Practice Manual ¶ C.11.1.1.

[10] 2021 UN Practice Manual Part D.

3. UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation

December 22, 2023, the United Nations General Assembly adopted resolution 78/230, “Promotion of inclusive and effective international tax cooperation at the United Nations.” The General Assembly directed that the UN develop a framework convention on international tax cooperation, which is fully inclusive for all UN member countries, most specifically, the non-OECD countries. Its design and drafting aim is to make international tax cooperation more accessible for non-OECD members and thus effective for all and also to accelerate the implementation of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Inclusive and effective participation in international tax cooperation requires procedures that take into account the diverse needs, priorities, and capacities of all countries, enabling them to contribute meaningfully to norm-setting processes without undue restrictions and to receive support in doing so, including the opportunity to participate in agenda-setting, debates, and decision-making.

For three weeks through August of 2024, a Member State-led, open-ended ad hoc intergovernmental committee drafted the terms of reference for the framework convention.[1] The terms of reference were finalized and recommended to the General Assembly.[2]

Protocols are separate, legally binding instruments under the framework convention to implement or elaborate on the framework convention. Each party to the framework convention should have the option to become a party to a protocol on any substantive tax issue, either at the time of becoming a party to the framework convention or at a later date. The subject of early protocols will be decided at the organizational session of the intergovernmental negotiating committee and drawn from the following specific priority areas: (a) taxation of the digitalized economy; (b) measures against tax-related illicit financial flows; (c) prevention and resolution of tax disputes; and (d) addressing tax evasion and avoidance by high-net-worth individuals and ensuring their effective taxation in the relevant Member States. Moreover, protocols addressing the following topics may also be considered: (a) tax cooperation on environmental challenges, (b) exchange of information for tax purposes, (c) mutual administrative assistance on tax matters, and (d) harmful tax practices.

The framework convention negotiating committee will meet for two weeks at least thrice annually in 2025, 2026, and 2027 to submit the final text of the framework convention and the two early protocols to the General Assembly for its consideration in the first quarter of the eighty-second session 2028.

[1] Second Session, Ad Hoc Committee to Draft Terms of Reference for a United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation, available at https://financing.desa.un.org/un-tax-convention/second-session.

[2] Available at https://financing.desa.un.org/sites/default/files/2024-08/Chair%27s%20proposal%20draft%20ToR_L.4_15%20Aug%202024____.pdf.

4. What About the Next Four Years (2025-2029) - An Overview of the UN's 31st Session (October 2025)

A United Nations tax committee of 25 experts, drawn from the staff of member states’ tax authorities, is currently meeting in Geneva this week to set its agenda for the next four years. The talks cover challenging global tax issues, including taxing tech giants and curbing corporate tax avoidance, as well as governments leveraging AI for tax audits and implementing green levies – issues with high stakes for both developing countries and U.S. multinationals.

The 31st session of the United Nations Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters runs from October 21 to 24, 2025 at the U.N. Headquarters Office of Geneva. This committee, often referred to as the UN Tax Committee, is a technical body of 25 independent experts (drawn from national tax authorities) that develops guidance on international tax policy and administration, with a special focus on the needs of developing countries. Committee members, appointed for a 2025–2029 term, come from diverse regions and serve in their personal capacities (they are nominated by governments but do not represent them directly). The group’s mandate is to help countries craft “stronger and forward-looking” tax policies suited to a globalized, digital economy, while preventing double taxation and curbing tax evasion and avoidance. In practice, the UN Tax Committee produces practical tools, including a competing model tax treaty (to the OECD version), a negotiations handbook for developing countries to approach tax treaties, and tax-regime specific handbooks (e.g. transfer pricing; extractive industries; dispute resolution), aimed at strengthening countries’ tax systems and boosting domestic resource mobilization (raising revenue at home) for development. This week’s gathering marks the first meeting of the newly appointed membership. The primary focus of the agenda is to decide the Committee’s work program for the next four years and set timeframes for deliverables.[1]

Stakeholders, including national governments, academic experts, civil society organizations, and private sector representatives, have submitted a wide range of proposals aimed at modernizing global tax norms for the Committee’s 2025–2029 work program. While many contributions revisit established debates such as the taxation of multinational technology corporations and the mitigation of corporate tax avoidance, others highlight emergent concerns pertaining to artificial intelligence (“AI”), health-related taxes, informal economies, and gender equity in taxation. This breadth of input evidences the increasing intersection of tax policy with developmental, technological, and social considerations, bearing potential implications for jurisdictions including the United States.

[1] United Nations, Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, Provisional Agenda of the Thirty-First Session (21–24 Oct. 2025, Geneva).

4.1 From Digital Taxes to Green Levies: The Usual Suspects (and More)

A significant proportion of submissions advocate for the continued development of digital economy taxation, focusing on the allocation of taxing rights over corporate profits earned via online activities in countries where a company maintains users or customers but lacks physical presence. Of fifty-one written inputs received, thirty-eight addressed taxation of digital services or related “nexus without presence” issues. Many developing countries are seeking enhanced source-based taxing rights over technology multinationals, building on recent UN initiatives such as Article 12B which targets taxation of digital services and the conceptualization of “digital permanent establishment.”[1] Relatedly, numerous stakeholders advocate for stricter transfer pricing regulations to curb profit shifting by multinational enterprises, primarily through the complex valuation of intangibles and intra-group transactions, which facilitate the relocation of profits to low-tax jurisdictions and result in substantial revenue losses for governments.[2] There is considerable support for adopting simplified, formulaic profit allocation methods, as opposed to the current arm’s-length principle, which is widely viewed as both administratively burdensome and susceptible to manipulation.[3] Some contributors further propose the creation of safe harbors or shared databases of comparable pricing data to help developing nations audit multinational activities.

Environmental taxation has also emerged as a priority, with over a dozen submissions—including those from France and several African states—requesting comprehensive guidance on carbon pricing, the taxation of carbon credits, and the structuring of green incentives.[4] Recent UN work, including the publication of the Carbon Taxation Handbook, marks significant progress. Yet, stakeholders are seeking additional resources, including model carbon tax frameworks, assistance in navigating the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, and recommendations regarding the taxation of emissions from the aviation sector.[5] These developments reflect a broader movement toward “greening” tax systems, which simultaneously generate revenue and incentivize sustainable behaviors.

Tax fairness and transparency remain central themes, with particular advocacy from U.S.-based organizations. For example, the Washington, D.C.-based FACT Coalition has urged the UN to promote public country-by-country reporting of corporate profits and tax payments, arguing that such disclosures would benefit developing countries that currently receive information only through restrictive and confidential intergovernmental exchanges.[6] Presently, the United States shares multinational tax reports with only two African nations under strict secrecy provisions, thereby limiting broader access.[7] The FACT Coalition contends that public reporting would eliminate costly legal barriers and facilitate oversight by tax authorities and investigative journalists, ultimately enhancing corporate accountability. Similarly, civil society groups from Latin America and Africa have called for the establishment of public beneficial ownership registries to expose illicit financial flows, a global transparency initiative that the United States has tentatively supported through measures such as the Corporate Transparency Act.[8]

While these established issues—digital taxation, corporate avoidance, environmental taxes, and transparency—already present substantial challenges, the Committee’s agenda has expanded further in response to new stakeholder concerns. Notably, the feedback from the thirty-first session reveals the emergence of topics that have seldom been addressed in prior international tax forums. The following section examines several of these new themes and their significance, including for U.S. policy.

[1] United Nations, Dept. of Econ. & Soc. Affairs, Article 12B: Income from Automated Digital Services, in United Nations Model Double Taxation Convention between Developed and Developing Countries: 2021 Update (2021) (introducing a new treaty provision to tax digital services).

[2] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations 2022

[3] U.N. Committee of Experts on Int’l Tax Matters, Secretariat Note on Taxation of the Digitalized and Globalized Economy, U.N. Doc. E/C.18/2025/CRP.24 (Oct. 7, 2025), at 2–3.

[4] United Nations, Financing for Sustainable Development Office, “Environmental Taxation” Submissions (Oct. 2025) (compiling stakeholder proposals for guidance on carbon pricing, carbon credit taxation, and green incentives).

[5] United Nations Dept. of Econ. & Soc. Affairs, Carbon Taxation Handbook (2024) (a 204-page technical handbook on designing carbon taxes in developing countries, produced in cooperation with USAID).

[6] Financial Accountability & Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition, Submission to the U.N. Tax Committee on Public Country-by-Country Reporting (Sept. 2025) (urging adoption of public reporting of multinationals’ tax payments).

[7] Id. at 3 (noting that as of 2025 the United States shares corporate tax reports with only two African nations – Mauritius and South Africa – under strict confidentiality, limiting broader African access)

[8] Corporate Transparency Act, Pub. L. No. 116-283, 134 Stat. 4604 (2021) (codified at 31 U.S.C. §§ 5331–5333) (establishing U.S. beneficial ownership disclosure requirements.

4.2 Taxing the Rise of AI and New Technologies

Artificial Intelligence has rapidly ascended as a focal point in international tax discourse.[1] Stakeholders note that AI is revolutionizing tax administration, from enhancing compliance and fraud detection to automating audit processes, and urge the UN to ensure that developing countries are not left behind in this technological transition. AI tools offer the potential to analyze vast datasets, automate routine tasks, and improve taxpayer services; however, resource-constrained nations often lack the technical expertise and funding necessary to implement such systems, raising concerns about a widening “tax tech” divide. Experts have recommended that the Committee develop guidelines or establish a dedicated task force on AI in tax administration, focusing on best practices for algorithmic design, data privacy safeguards, and vendor selection by revenue authorities. Additionally, the protection of taxpayer rights in the context of AI-driven audits has been emphasized, with proposals suggesting that individuals flagged by AI for audit should retain the right to human review.[2] Absent global standards, the deployment of AI in tax administration risks outpacing the evolution of legal protections.

AI is not solely a tool for tax authorities; it is also giving rise to new tax bases and avenues for tax avoidance. As AI-enabled enterprises generate profits through intangible means, countries are debating mechanisms for capturing a fair share of this value.[3] The debate mirrors ongoing discussions regarding the taxation of highly digitalized businesses, many of which are headquartered in the United States. It has prompted consideration of an “AI tax” or the inclusion of AI services within digital services tax regimes.[4] Some scholars have even proposed a “robot tax”—a levy on corporations that substitute human labor with AI and automation—as a means of addressing growing economic inequality.[5] Although consensus on such innovative tax measures remains elusive, their appearance on the UN agenda signals the urgency with which policy must adapt to technological change.[6] For U.S. policymakers, these developments may foreshadow future disputes, as the United States has opposed unilateral digital services taxes and could similarly resist the imposition of AI-specific taxes aimed at major Silicon Valley firms.[7] Nonetheless, the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) has begun deploying AI systems to enforce existing laws; for instance, in the current year, the IRS announced the use of AI to detect tax evasion patterns among large partnerships, a move that has prompted legislative scrutiny regarding privacy implications.[8] As AI continues to reshape economic activity, the UN Tax Committee is poised to play a critical role in formulating guidance on the responsible taxation and utilization of this technology at the global level.[9]

[1] U.N. Committee of Experts on Int’l Tax Matters, Secretariat Note on Tax-Related Artificial Intelligence Issues, U.N. Doc. E/C.18/2025/CRP.25 (Oct. 7, 2025), at 1 (observing that Artificial Intelligence is a “powerful tool for tax administrations” but comes with significant risks and resource gaps for developing countries).

[2] Pramod Kumar Siva, Legal and Regulatory Implications of Agentic AI in Tax Administration, 118 Tax Notes Int’l 1711 (June 16, 2025) (analyzing privacy, bias, due process, and accountability challenges posed by autonomous AI in tax enforcement), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5333340.

[3] U.N. Committee of Experts on Int’l Tax Matters, Secretariat Note on Taxation of the Digitalized and Globalized Economy, supra note 9, at 6 (noting that some submissions proposed expanding digital services taxes to cover AI-enabled services, mirroring debates on taxing highly digitalized businesses).

[4] See, e.g., BEPS Monitoring Group, Stakeholder Input to UN Tax Committee Work Programme 2025–2029 (Sept. 2025), at 2–3 (advocating inclusion of digital services and possibly certain AI-based services in new taxing-rights rules); Tax Justice Network, Submission to UN Tax Committee (Sept. 2025), at 4 (proposing that digital services tax measures be considered if consensus on Pillar One falters).

[5] Ryan Abbott & Bret Bogenschneider, “Should Robots Pay Taxes?”, 12 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 145, 146–53 (2018) (exploring the rationale for a tax on robots or AI that displace human labor).

[6] U.N. Committee of Experts on Int’l Tax Matters, Secretariat Note on Taxation of the Digitalized and Globalized Economy, supra note 9, at Annex (reflecting that even though novel ideas like an “AI tax” lack consensus, their emergence on the UN agenda underscores the urgency of adapting tax policy to technological change).

[7] U.S. Dep’t of the Treasury, Press Release: United States and Five European Countries Extend Transition Agreement on Digital Services Taxes (Feb. 15, 2024) (reaffirming U.S. opposition to unilateral DSTs and extending a moratorium on DST measures pending a multilateral OECD solution).

[8] I.R.S. News Release IR-2023-166 (Sept. 8, 2023) (announcing a sweeping enforcement initiative using AI to detect tax evasion patterns – including opening audits of 75 large partnerships – as part of efforts to restore fairness in the tax system.

[9] Letter from Rep. Jim Jordan, Chairman, H. Comm. on the Judiciary, & Rep. Harriet Hageman to Hon. Janet L. Yellen, U.S. Treasury Secretary (Mar. 20, 2024) (inquiring into the IRS’s use of AI to monitor taxpayers’ financial data without warrants, and citing concerns of “AI-powered warrantless financial surveillance”).

4.3 Health Taxes for Development – Tobacco, Sugar, and Beyond

Several developing country submissions implored the Committee to champion health taxes – excise taxes on products like tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks that raise revenue and improve public health. Such taxes are sometimes called “sin taxes,” but stakeholders frame them as smart fiscal policy: easy to administer, hard to evade, and yielding a double dividend of funds and healthier populations.[1]

The African Alliance for Health Research and Economic Development, for example, noted that many low-income countries struggle to finance healthcare and climate adaptation, and argued that targeted levies on harmful products could help fill the gap. They urged the UN experts to develop technical guidance on designing and implementing health-related taxes (on tobacco, alcohol, sugary drinks) and to share best practices on monitoring their impacts. Such guidance could include model legislation for tobacco taxes or sugar-sweetened beverage taxes, as well as advice on setting rates high enough to deter consumption but not so high as to encourage black markets.[2]

The push for health taxes also has a U.S. angle. In the United States, federal and state governments have long taxed cigarettes and alcohol (with proven public health benefits), and cities like Philadelphia and Berkeley pioneered soda taxes. American health advocates, including some foundations and researchers, have promoted similar measures abroad as a win-win for achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Notably, no U.S. government entity weighed in at the UN to advocate for health taxes; the submissions primarily came from African and international health groups. However, U.S.-based organizations, such as Bloomberg Philanthropies, have funded technical support for such taxes globally. For the UN Tax Committee, incorporating health taxes into its work program would align with broader development priorities and World Health Organization recommendations, signaling that tax policy is not just about macroeconomics, but also about saving lives. It might even nudge U.S. policymakers to consider strengthening health-related taxes at home (e.g., revisiting federal soda tax proposals) if framed as part of a global best practice.

[1] World Health Organization, WHO Technical Manual on Tobacco Tax Policy and Administration, at 1–3 (2021) (noting that well-designed health taxes on products like tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks can both raise revenues and significantly reduce harmful consumption – a “double dividend”).

[2] African Alliance for Health, Research and Economic Development, Stakeholder Submission on Health Taxes (Sept. 2025) (arguing that excise taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks could help low-income countries finance healthcare and climate adaptation, and urging the UN to develop model health tax legislation).

4.4 Minimum Taxes and the “STTR” Debate

Even as the OECD’s global 15 percent minimum corporate tax (Pillar Two) inches toward implementation, developing countries are advocating tweaks to ensure it works for them. A key request in the UN submissions is support for the Subject To Tax Rule (STTR) – a treaty-based measure that allows source countries to impose a withholding tax on certain cross-border payments (such as interest and royalties) that would otherwise go untaxed or lightly taxed in the recipient’s country. Essentially, STTR is designed to prevent “double non-taxation” by ensuring a modest tax (typically 9 percent) on these outbound payments. The UN Tax Committee has approved its own version of an STTR, and stakeholders like Nigeria’s Federal Inland Revenue Service urged that it be prioritized and broadened. Nigeria noted some current proposals are too limited – for example, the OECD’s version excludes many transactions and has complex carve-outs – and it recommended a simpler rule to catch any payment that isn’t taxed because the payee lacks a permanent establishment in the source country. Such a rule would strengthen developing countries’ hand in taxing services or royalties being paid to offshore affiliates.[1]

Alongside STTR, there were calls to refine the implementation of the global minimum tax. Some civil society groups from Latin America argued that the 15 percent rate might be too low to curb harmful tax competition, and that developing nations should explore complementary measures. One idea floated is a Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax (DMTT) – basically, if a multinational’s local effective rate falls below the agreed minimum, the source country itself would collect the top-up to 15%, rather than leaving that to the company’s home country. This aligns with OECD Pillar Two rules; however, developing countries seek UN guidance to ensure they can easily adopt DMTTs and avoid missing out on revenue. Another idea (championed by an academic from India) is to consider a “Significant Economic Presence” concept or other alternatives if the traditional permanent establishment threshold becomes obsolete in a digitalizing economy. The subtext in many submissions is wariness that the OECD-led deal, while a milestone, might skew benefits toward rich countries unless additional source-based tools, such as a robust STTR, are in place. In fact, analysis shows the UN’s simpler STTR would likely yield more revenue for developing countries than the OECD’s narrower version.[2]

For the United States, these discussions are highly pertinent. The U.S. helped design Pillar Two but has not yet implemented it domestically, and it has an extensive network of tax treaties that could be affected by an STTR multilateral instrument. U.S. companies could face those source-country withholdings if an UN-driven STTR becomes common. At the same time, the U.S. Congress’ reluctance to adopt the 15 percent minimum (due to partisan gridlock) means the U.S. might see other countries scoop up tax revenue that could have gone to the IRS – a scenario some lawmakers want to avoid. The UN Tax Committee’s work on these rules could thus influence the global playing field on which U.S. firms and tax policymakers operate. Any concrete UN guidance or model treaties on STTR and minimum taxes will be closely monitored by both multinationals and Treasury officials.

[1] Federal Inland Revenue Service (Nigeria), Stakeholder Submission to UN Tax Committee (Sept. 2025) (calling for prioritization of a robust Subject-to-Tax Rule and noting shortcomings of the OECD’s 9 percent STTR scope).

[2] South Centre & G-24, Press Release: Country-Level Revenue Estimates – A Comparative Analysis of UN and OECD Subject to Tax Rules for 65 Member States (July 23, 2025) (reporting that the UN’s broader STTR would yield substantially higher tax revenues for developing countries than the narrower OECD version).

4.5 Balancing Ambition with Practicality

AAs the UN Tax Committee convenes in late October for its 31st session (now with a new 25-member roster of experts from around the world), it faces the daunting task of sifting through this rich array of stakeholder proposals. There is a clear momentum toward a more inclusive international tax dialogue – one that not only continues technical work on treaties and transfer pricing, but also integrates tax with digital innovation, health policy, climate action, and social justice. For an advisory body that operates by consensus and whose outputs are often non-binding, selecting priorities will require striking a balance between ambition and feasibility. Not every idea will make the cut; some issues might be referred to other forums (for instance, the IMF or World Bank may take on informal sector taxation, or the UN’s New York process on the tax convention may tackle overarching principles like global wealth taxation that were also floated).

Stakeholders are clearly thinking beyond the status quo. Whether it’s carving out a role for AI in easing tax compliance burdens, enacting excise taxes that fight diabetes and smoking, or rewriting tax rules to account for remote workers and carbon traders, the submissions urge the Committee to be forward-looking. There is also an implicit call for the UN to assert a more decisive leadership role in global tax norm-setting, reflecting the frustration of developing countries with the slower, consensus-bound OECD process. The recent UN General Assembly resolution to initiate negotiations on a Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation heightens the stakes; the Committee’s work program may shape what ultimately goes into that treaty.

For American observers, who are traditionally more focused on domestic tax issues or OECD initiatives, the flurry of activity at the UN is worth paying attention to. U.S. companies and civil society alike have a stake in the game: how digital profits are distributed, how transparent corporate finances are, and how new taxes (from carbon to AI) are designed will all impact the U.S. in the long run. Encouragingly, at least one U.S.-led coalition (FACT) and several U.S. academics engaged with this UN process, emphasizing that global tax fairness can advance both development and American interests by leveling playing fields. The tone of the submissions is cooperative mainly – stakeholders aren’t looking to punish any one country, but to ensure all countries, especially poorer ones, have the tools to raise revenue fairly in the 21st century.

As the session unfolds, expect detailed agenda items on topics such as updating the UN Model Tax Convention, enhancing tax dispute resolution, and providing new guidance on tax incentives. However, also expect the unexpected: discussions of topics like a “Gender and Taxation” toolkit or an AI ethics charter for tax administrations could emerge, which would have been unthinkable in this arena just a decade ago. The breadth of stakeholder input ensures that Committee members will have exposure to diverse ideas. If they manage to translate even a portion into concrete outputs – say, a new UN handbook on health taxes or an outline for taxing remote work – it could mark a significant broadening of international tax cooperation. In the end, the 31st session’s expanded brief shows that tax is no longer a dry, isolated field; it’s at the heart of debates on sustainable development, technology, and equity. And what happens in this realm will reverberate far beyond the United Nations, reaching policymakers in the OECD and capitals of member states, such as Washington, Paris, Lagos, Beijing, Mumbai, Brasilia, and everywhere in between.

You may also like